Scanian War

This August 2024 needs additional citations for verification. (August 2024) |

| Scanian War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Franco-Dutch War and the Northern Wars | |||||||||

Battles (left to right from top): | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Supported by: |

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

The Scanian War (Danish: den Skånske Krig; Norwegian: den skånske krig; Swedish: det Skånska kriget; German: Schonischer Krieg) was a part of the Northern Wars involving the union of Denmark–Norway, Brandenburg and Sweden. It was fought from 1675 to 1679 mainly on Scanian soil, in the former Danish–Norwegian provinces along the border with Sweden, and in Northern Germany. While the latter battles are regarded as a theater of the Scanian war in English, Danish, Norwegian and Swedish historiography, they are seen as a separate war in German historiography, called the Swedish-Brandenburgian War (German: Schwedisch-Brandenburgischer Krieg).

The war was prompted by Swedish involvement in the Franco-Dutch War. Sweden had allied with France against several European countries. The United Provinces, under attack by France, sought support from Denmark–Norway. After some hesitation, King Christian V started the invasion of Skåneland (Scania, Halland, Blekinge, and sometimes also Bornholm) in 1675, while the Swedes were occupied with a war against Brandenburg. The invasion of Scania was combined with a simultaneous Norwegian front called the Gyldenløve War, forcing the defending Swedes to fight a two-front war in addition to their entanglements in the Holy Roman Empire.

The Danish objective was to retrieve the Scanian lands that had been ceded to Sweden in the Treaty of Roskilde, after the Northern Wars. Although the Danish offensive was initially a great success, Swedish counter-offensives led by the 19-year-old Charles XI of Sweden nullified much of the gain.

At the end of the war, the Swedish navy had lost at sea, the Danish army had been defeated in Scania by the Swedes, who in turn had been beaten in Northern Germany by the Brandenburgers. The war and the hostilities ended when Denmark's ally, the United Provinces, settled with Sweden's ally France and the Swedish king Charles XI married Danish princess Ulrike Eleonora, sister of Christian V. Peace was made on behalf of France with the treaties of Fontainebleau and Lund (Sweden and Denmark–Norway) and Saint-Germain-en-Laye (Sweden and Brandenburg), restoring most of the lost territories to Sweden.[2]

Background

[edit]Franco–Swedish alliance

[edit]In the 1660s and early 1670s, the Swedish Empire experienced a financial crisis. In hope of subsidies, the Swedish government, acting on behalf of king Charles XI of Sweden during his minority, had entered the anti-French Triple Alliance with the Dutch Republic and the Kingdom of England, which broke apart when Charles II of England rapproached France in 1670, after the War of Devolution.[4]

In April 1672, Sweden and France concluded an alliance, with France promising 400,000 riksdaler of subsidies in peace time, to be raised to 600,000 in war time, for Sweden maintaining a 16,000 men strong army in her German dominions. Also, Sweden maintained good relations to the Dukes of Holstein-Gottorp south of Denmark.[4]

By September 1674, Sweden had enlarged her army to 22,000 men after France had increased the subsidies to 900,000 riksdaler, which she threatened to withdraw if Sweden was not using this army, stationed in Swedish Pomerania, for an attack on her adversaries. By December, the Swedish army had grown to around 26,000 men, roughly half of which were stationed in garrisons in Bremen, Wismar and Pomerania while the rest were free to operate under Lord High Constable and field marshal Carl Gustaf Wrangel.[5]

Anti-Franco–Swedish alliance

[edit]Another defensive alliance formed in September 1672 between Denmark–Norway, Emperor Leopold I, the Electorate of Brandenburg, and the duchies of Brunswick-Celle, Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel and Hesse-Cassel. This alliance maintained an army of 21,000 foot and 10,500 horse, and since May 1673, an additional 12,000 men and twenty vessels maintained with Dutch subsidies.[6] At that time in history, Brandenburg was the second most powerful German state (the most powerful being Austria), and maintained its own standing army of 23,000 men.[7]

The Netherlands had been attacked by the French army in 1672, known as the rampjaar, and the ensuing Franco-Dutch War would only be concluded by the Treaties of Nijmegen in 1678. Roi soleil Louis XIV intended to weaken the anti-French alliance by engaging them on their eastern frontiers: he supported John Sobieski, candidate for the Polish throne, he also supported a contemporary revolt of nobles in Hungary, and aimed at binding the Brandenburgian army in a war with Sweden.[3]

War on land

[edit]Tactics

[edit]At the time of the Scanian War Swedens armed forces were oriented around cavalry as the main assault force with infantry filling a defensive role supported by cavalry units. Being on the offensive were preferred in a battle. In a set of regulations written in 1676 by Rutger von Ascheberg, the cavalry were to rush the enemy and get in so close that they could see the whites of their eyes before firing their pistols at the enemy. After that swords were to be drawn and the attack pressed.[8]

In Northern Germany

[edit]Swedish–Brandenburger War

[edit]

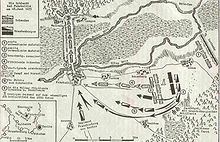

In December 1674, Louis XIV of France called upon Sweden to invade Brandenburg. Wrangel advanced into the Uckermark, a region on the Brandenburg–Pomeranian frontier, securing quarters for his forces until the weather would permit him to turn westwards to Hanover. Frederick William I, Elector of Brandenburg received the news in the Rhine valley, and turned northeast to confront Wrangel. On 18 June (OS) or 28 June (NS) the armies met in the Battle of Fehrbellin.[5]

The Fehrbellin affair was a mere skirmish, with actual casualties amounting to fewer than 600 men on each side—but it was a defeat by a numerically inferior force from a territory for which Sweden had little regard. As a result of this defeat, Sweden appeared vulnerable, encouraging neighbouring countries that had suffered invasion by Sweden in the prior Swedish campaigns to join in the Scanian War. Wrangel retreated to Swedish Demmin.[9]

When the United Provinces initially asked for Danish–Norway support against the French and their allies in the Franco-Dutch War, Danish–Norwegian King Christian V wanted to join them, and go to war with Sweden immediately to recapture the historically Danish provinces of Scania and Halland. Count Peder Griffenfeld, an influential royal adviser, advised against it, and instead advocated a more pro-France policy. But when the numerically superior Swedes lost the Battle of Fehrbellin on 28 June 1675, it was the first such defeat of Swedish forces since the Thirty Years' War. Christian V saw his chance, and overcoming Griffenfeld's opposition, attacked.[9]

Allied campaign against Bremen–Verden

[edit]The second largest Swedish garrison in North Germany, after Swedish Pomerania, was the twin Duchy of Bremen-Verden. For political reasons, and to prevent the Swedes from advertising and recruiting mercenaries, the Allies decided to conquer these two duchies. Denmark–Norway and Brandenburg–Prussia were joined by allies from the neighbouring imperial principalities of Münster and the Duchy of Brunswick-Lüneburg.

The campaign began on 15 September 1675 with an Allied advance into the two Swedish duchies. They rapidly captured one Swedish fortress after another. The Swedes were hampered by the high number of mainly German deserters because, after the imposition of the Imperial Ban it was forbidden to take up arms against member states of the Holy Roman Empire.

By the end of the year only the Swedish headquarters town of Stade and Carlsburg were still in Swedish hands. In November the Allies sent their troops into winter quarters with the result that the conquest of the last remaining Swedish strongholds had to wait until the following year. Stade did not surrender until 13 August 1676. This theatre of war was nevertheless only of secondary importance for the Allies and for Sweden.

Swedish Pomerania

[edit]

At this point, the Swedish empire in Germany began to crumble. In 1675, most of Swedish Pomerania and the Duchy of Bremen were taken by the Brandenburgers, Austrians, and Danes. In December 1677, the elector of Brandenburg captured Stettin. Stralsund fell on 11 October 1678. Greifswald, Sweden's last possession on the continent, was lost on 5 November. A defensive alliance with John III of Poland, concluded on 4 August 1677,[10] was rendered inoperative by the annihilation of Sweden's sea-power, the Battle of Öland, 17 June 1676; Battle of Fehmarn, June 1677, and the difficulties of the Polish king.

Danish–Norwegian reconquest of Scania

[edit]The Danish–Norway recapture of Scania (which had been captured by Sweden in 1658) started with the seizure of Helsingborg on 29 June 1676. Danish king Christian V brought 15,000 troops against a defending Swedish army of 5,000 men, who spread out over the province.

Initially the operation was a great success. Large parts of the local peasantry sided with Denmark and the outnumbered Swedish troops were in bad shape.

Town after town fell into the hands of the Danes–Norwegian and the Swedes had to retreat north to Sweden proper. In a month's time only the fortified town of Malmö remained under Swedish control.

The Gyldenløve War

[edit]Norwegian history records the campaigns in Norway (or in formerly Norwegian provinces) as the Gyldenløve War; it was named after Governor-General Ulrik Frederick Gyldenløve, who as commander-in-chief directed the Norwegian offensive. The Norwegian offensives were generally successful, but served only to offset the Danish setbacks elsewhere.[11]

1675 stalemate

[edit]Simultaneously with the Danish invasion, Norway's forces were marshaled along the border to force the Swedes to deal with the prospect of fighting a two-front war. A force of 4,000 Norwegians was concentrated at Fredrikshald under the command of General Russenstein, both protecting against any Swedish attempts to invade and threatening to retake the formerly Norwegian province of Bohuslän. The Swedish General Ascheberg took position at Svarteborg with 2,000 men. Operations along the Norwegian–Swedish border during 1675 were largely skirmishes to test strength, as mountain passes were well guarded. Gyldenløve then directed 1,000 men in galleys to proceed down the coast and cut off Ascheberg's supply route; as Ascheberg had intelligence of the effort, it was unsuccessful. Both armies went into winter quarters in the border districts.[11]

Gyldenløve's 1676 campaign

[edit]

In 1676 Gyldenløve personally led Norwegian forces in the field. His Norwegian army took and fortified the pass at Kvistrum and proceeded south, seizing Uddevalla with minimal opposition. Swedish forces provided significantly more resistance to the attack on Vänersborg, but Gyldenløve's forces captured it. From there his forces moved to Bohus where they were supplemented by General Tønne Huitfeldt's army of 5000 men.[11] Gyldenløve subsequently besieged the fortress, but was forced to retreat due to dwindling supplies.[12]

In early August a Danish–Norwegian expedition was sent north to take the town of Halmstad and then advance along the Swedish west coast to seek contact with General Gyldenløve's forces. This led to the Battle of Halmstad where Charles XI of Sweden won a decisive victory over the Danish mercenary force led by a Scotsman, General Jacob Duncan, effectively preventing the linking of forces. The Swedes then retreated north to gather more troops. Christian V brought his army to Halmstad and besieged the town for a couple of weeks but gave up and returned to winter quarters in Scania.

Recapture of Bohuslän

[edit]Despite the Danish forces' defeat at Fyllebro, the successful recapture of Scania allowed Norwegian troops to regain formerly Norwegian Bohuslän. During the winter of 1677, the Norwegian army was increased to 17,000 men, allowing operations to increase further. Gyldenløve captured the fortress at Marstrand in July and joined forces with General Løvenhjelm.[11]

The Swedes mounted a counteroffensive under the command of Magnus Gabriel De la Gardie, sending an army of 8,000 to expel the Norwegian forces. They were defeated by the Norwegians, and forced to retreat, holding only Bohus Fortress in Bohuslän.[11]

Reconquest of Jämtland

[edit]In August 1677, Norwegian forces of 2,000 men, led by General Reinhold von Hoven and General Christian Shultz also retook formerly Norwegian Jämtland.[11]

Although Bohuslän and Jämtland were former Norwegian provinces and the forces in both locations were well received by the native populations there, things went badly for Denmark–Norway in the Scanian campaigns, and the Norwegian forces withdrew when ordered to do so by King Christian V.[11]

War in Scania

[edit]On 24 October 1676, the Swedish king Charles XI marched back into Scania with an army of 12,000, forcing the Danes on the defensive. After a number of skirmishes the Danish army was badly beaten in the Battle of Lund on December 4. Despite gains by Gyldenløve in the north, the Swedish offensive of Charles XI tipped the scale. After failing to take Malmö and the defeat at the Battle of Landskrona the Danish Army in Scania was still not beaten, but the morale was definitely broken.

However the Danes held the fortified town of Landskrona and was able to ship in more Dutch and German mercenaries and in July 1678 Christian V marched east to rescue the diminishing Danish garrison in the town of Kristianstad besieged by the Swedes. After facing the whole Swedish army on the plain west of Kristianstad Christian V opted not to give battle but to retreat back to Landskrona and evacuate all his troops from Scania.

War at sea

[edit]

Battle of Öland

[edit]The war was also fought at sea. In the Battle of Öland, 1 June 1676, the Danish and Dutch fleet won a great victory over the Swedes, sinking one of the largest naval vessels at that time, Kronan. With the victory they got control of the Baltic Sea.

Battle of Fehmarn

[edit]The Danes–Norwegian won another significant victory in the Battle of Fehmarn on 31 May 1677. The battle was located between Fehmarn and Warnemünde, north of modern-day Germany. The Danes–Norwegian had been blockading a Swedish squadron in Göteborg (Gothenburg), and each side had been sending fleets out regularly in the hope of a decisive victory at sea. The Swedish ships, under Erik Carlsson Sjöblad, left to return to the Baltic Sea and there met a larger Danish–Norwegian squadron under Admiral Niels Juel. The action started in the evening of the 31st and continued until the next morning. It was an almost complete Danish–Norwegian victory. Several Swedish ships were captured, most as they tried to flee, and one was run aground and burned.

Battle of Køge bay

[edit]The control at sea was secured a year later, when the Danish–Norwegian fleet, led by Niels Juel, again defeated the Swedish fleet at the Battle of Køge Bay, near Copenhagen. The Swedes lost over 3,000 men in this engagement, while the Danish–Norwegian only suffered some 375 casualties. The Danish–Norwegian success at sea hindered the Swedish ability to move troops between northern Germany and Sweden.

Peace

[edit]Peace was negotiated between France (on behalf of Sweden) and Denmark–Norway at the Treaty of Fontainebleau on 23 August 1679. The peace, which was largely dictated by France, stipulated that all territory lost by Sweden during the war should be returned. Thus the terms formulated at the Treaty of Copenhagen remained in force. It was reaffirmed by the Treaty of Lund, signed by Denmark-Norway and Sweden themselves. Denmark received minor war reparations from Sweden and returned Swedish Rügen. Likewise, the Electorate of Brandenburg had to return most of her gains, Bremen-Verden and Swedish Pomerania, with the exception of most of Swedish Pomeranian territory east of the Oder, to Sweden on behalf of France in the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye.[13]

In Scania itself, however, the war had a devastating effect in raising the hopes of the pro-Danish guerilla known as Snapphane and their sympathisers, who thereupon suffered savage repression from the reinstated Swedish authorities.

Outcome

[edit]The exact result of the war is disagreed upon by scholars. Some sources view the war as a Swedish defeat,[14] with other sources viewing the war as inconclusive.[15][16][17][18] Historian Michael Fredholm von Essen also claims that one could argue that the real winner of the Scanian war was the French king, Louis XIV along with Brandenburg.[16] There are also sources that claim the Swedes won the war.[19][20][21][22] The result of the war and the terms of the peace treaties were a large dissapointment for Denmark, being referred to as "En skiden og skammelig fred" by a priest in Copenhagen.[23]

See also

[edit]- Dominium maris baltici – Political aim

References

[edit]- ^ Sundberg, Ulf (2010). Sveriges krig 1630–1814 [Sweden's wars 1630–1814] (in Swedish). Svenskt militärhistoriskt bibliotek. p. 178. ISBN 9789185789634.

- ^ The Scanian War 1675–79 Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Educational site for high schools created by Oresundstid Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b Hermann Kinder, Werner Hilgemann, ed. (2009). Weltgeschichte. Von den Anfängen bis zur Französischen Revolution. dtv Atlas (in German). Vol. I (39 ed.). Munich: dtv. p. 259. ISBN 978-3-423-03001-4.

- ^ a b Frost, Robert I (2000). The Northern Wars. War, State and Society in Northeastern Europe 1558–1721. Longman. p. 209. ISBN 978-0-582-06429-4.

- ^ a b Frost, Robert I (2000). The Northern Wars. War, State and Society in Northeastern Europe 1558–1721. Longman. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-582-06429-4.

- ^ Frost, Robert I (2000). The Northern Wars. War, State and Society in Northeastern Europe 1558–1721. Longman. pp. 209–210. ISBN 978-0-582-06429-4.

- ^ Hermann Kinder, Werner Hilgemann, ed. (2009). Weltgeschichte. Von den Anfängen bis zur Französischen Revolution. dtv Atlas (in German). Vol. I (39 ed.). Munich: dtv. p. 263. ISBN 978-3-423-03001-4.

- ^ Rystad, Göran, ed. (2005). Kampen om Skåne (in Danish) (Ny rev. utg. ed.). Lund: Historiska media. ISBN 978-91-85057-05-4.

- ^ a b c Lisk, Jill (1967). The Struggle for Supremacy in the Baltic: 1600–1725. Funk & Wagnalls, New York. Retrieved 17 May 2009.

- ^ Bain, Robert N., Scandinavia: A Political History of Denmark, Norway and Sweden from 1513 to 1900, Cambridge University Press, 1905, p. 297.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gjerset, Knut (1915). History of the Norwegian People, Volumes II, pp. 253–261. The MacMillan Company. Retrieved 16 May 2009.

- ^ Essen 2019, pp. 114–115. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFEssen2019 (help)

- ^ Asmus, Ivo (2003). "Das Testament des Grafen – Die pommerschen Besitzungen Carl Gustav Wrangels nach Tod, förmyndarräfst und Reduktion". In Asmus, Ivo; Droste, Heiko; Olesen, Jens E. (eds.). Gemeinsame Bekannte: Schweden und Deutschland in der Frühen Neuzeit (in German). Berlin-Hamburg-Münster: LIT Verlag. p. 211. ISBN 3-8258-7150-9.

- ^ Delmarcel, Guy (2002). Flemish Tapestry Weavers Abroad: Emigration and the Founding of Manufactories in Europe : Proceedings of the International Conference Held at Mechelen, 2-3 October 2000. Leuven University Press. p. 107. ISBN 978-90-5867-221-6.

- ^ Gibler, Douglas M. (15 October 2008). International Military Alliances, 1648-2008. CQ Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-60426-684-9.

- ^ a b Essen, Michael Fredholm von (2019). Charles XI's War: The Scanian War Between Sweden and Denmark, 1675-1679. Helion Limited. p. 218. ISBN 978-1-911628-00-2.

- ^ "Skånska kriget | Historia | SO-rummet". www.so-rummet.se (in Swedish). 3 June 2024. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ Bodart, Gaston (1908). Militär-historisches Kriegs-Lexikon (1618-1905). Harvard University. Wien und Leipzig, C. W. Stern. p. 766.

- ^ Perrie, Maurren (2006). The Cambridge history of Russia. Volume 1: From early Rus' to 1689. Cambridge university Press. p. 507. ISBN 0-521-81227-5.

- ^ Isacson, Claes-Göran (2000). Skånska kriget 1675-1679 (in Swedish). Historiska media. p. 110. ISBN 978-91-88930-87-3.

Nu, hösten 1679, går Sverige in i en lugn fredperiod. Även om man inte trodde på den eviga freden utan faktiskt började rusta upp igen syns inget nytt krig vid horisonten. Ändå skulle det bara ta 21 år innan danskarna kommer tillbaka med eld och brand. De hade förlorat detta krig men hoppet om Skåne tillbaka var ej släckt.

- ^ Kiser, Edgar; Drass, Kriss A.; Brustein, William (1994). "The Relationship Between Revolt and War in Early Modern Western Europe". Journal of Political & Military Sociology. 22 (2): 305–324. ISSN 0047-2697. JSTOR 45371312.

- ^ Katajala, Kimmo (2005). Suurvallan rajalla: IHMISIÄ RUOTSIN AJAN KARJALASSA [On the border of a superpower: People in Karelia During the Swedish Time] (in Finnish). Finnish Literature Society. p. 227. ISBN 9517466986.

Käännekohta eteläisten maakuntien liittämisessä valtakuntaan oli Tanskan kanssa 1675–1679 käyty sota. Ruotsille annetusta uskollisuudenvalasta huolimatta nousi rahvaan joukosta avoin vastarinta, snapphane-liike eli "siepposissit". Snapphane liike motivoi sissitoimintansa ruotsalaisten toimeenpanemien uudistusten vastaisuudella. Ruotsi voitti sodan ja itsevaltiaaksi noussut Kaarle XI ryhtyi kovalla kädellä yhtenäistämään valtakuntaansa, myös eteläisissä maakunnissa.

- ^ Rystad 2005, p. 317. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFRystad2005 (help)

Works cited

[edit]- Rystad, Göran (2005). Kampen om Skåne [Battle for Scania] (in Swedish). Lund: Historiska Media. ISBN 9789185057054.

- Essen, Michael Fredholm von (2019). Charles XI’s War: The Scanian War Between Sweden and Denmark, 1675-1679. Century of the Soldier. Helion & Company. ISBN 9781911628002.

External links

[edit]- Scanian War

- Conflicts in 1675

- Conflicts in 1676

- Conflicts in 1677

- Conflicts in 1678

- Conflicts in 1679

- 17th century in Denmark

- 17th century in Norway

- 17th century in Skåne County

- 1675 in Denmark

- 1675 in Norway

- 1675 in Sweden

- Northern Wars

- History of Scania

- Wars involving Denmark

- Wars involving France

- Wars involving the Holy Roman Empire

- Wars involving Norway

- Wars involving Sweden

- Wars involving the Dutch Republic

- Wars involving the Netherlands

- Denmark–Sweden relations

- Denmark–France relations

- Wars involving Brandenburg-Prussia