Bakumatsu

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Japan |

|---|

|

Bakumatsu (幕末, 'End of the bakufu') were the final years of the Edo period when the Tokugawa shogunate ended. Between 1853 and 1867, under foreign diplomatic and military pressure, Japan ended its isolationist foreign policy known as sakoku and changed from a feudal Tokugawa shogunate to the modern empire of the Meiji government. The major ideological-political divide during this period was between the pro-imperial nationalists called ishin shishi and the shogunate forces, which included the elite shinsengumi swordsmen.

Although these two groups were the most visible powers, many other factions attempted to use the chaos of bakumatsu to seize personal power.[1] Furthermore, there were two other main driving forces for dissent: first, growing resentment on the part of the tozama daimyō (or outside lords), and second, growing anti-Western sentiment following the arrival of Matthew C. Perry. The first related to those lords whose predecessors had fought against Tokugawa forces at the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600, after which they had been permanently excluded from all powerful positions within the shogunate. The second was to be expressed in the phrase sonnō jōi, or "revere the Emperor, expel the barbarians". The turning point of the Bakumatsu was during the Boshin War and the Battle of Toba–Fushimi when pro-shogunate forces were defeated.[2]

Background

[edit]Frictions with foreign powers

[edit]Frictions with foreign shipping led Japan to take defensive actions from the beginning of the 19th century. Western ships were increasing their presence around Japan due to whaling activities and the trade with China. They were hoping for Japan to become a base for supply or at least a place where shipwrecks could receive assistance. The incident in Nagasaki Harbour where the Royal Navy frigate HMS Phaeton demanded supplies from the harbour chief in 1808 shocked the Tokugawa government, who ordered the ports to be even more tightly guarded.[3] In 1825, the Edict to expel foreigners at all cost (異国船無二念打払令, Ikokusen Muninen Uchiharairei, "Don't think twice" policy) was issued by the shogunate, prohibiting any contacts with foreigners; it remained in place until 1842.

Meanwhile, Japan endeavoured to learn about foreign sciences through rangaku ("Western studies"). To reinforce Japan's capability to carry on the orders to repel Westerners, some such as the Nagasaki-based Takashima Shūhan managed to obtain weapons through the Dutch at Dejima, such as field guns, mortars and firearms.[3] Domains sent students to learn from Takashima in Nagasaki, from Satsuma Domain after the intrusion of an American warship in 1837 in Kagoshima Bay, and from Saga Domain and Chōshū Domain, all southern domains mostly exposed to Western intrusions.[4] These domains also studied the manufacture of Western weapons. By 1852 Satsuma and Saga had reverberatory furnaces to produce the iron necessary for firearms.[4]

Following the Morrison incident involving the Morrison under Charles W. King in 1837, Egawa Hidetatsu was put in charge of establishing the defense of Tokyo Bay against Western intrusions in 1839.[5] After the humiliating defeat suffered by Qing China in the First and Second Opium Wars, many Japanese officials realized that their traditional methods would be no match for western powers. To deal with Western powers on equal terms, Western guns were studied and demonstrations made in 1841 by Takashima Shūhan to the Tokugawa government.[3]

A national debate was already taking place about how to better avoid foreign incursions. Some such as Egawa claimed that it was necessary to use the foreigners' techniques to repel them. Others, such as Torii Yōzō argued that only traditional Japanese methods should be employed and reinforced.[6] Egawa argued that just as Confucianism and Buddhism had been introduced from abroad, it made sense to introduce useful Western techniques.[6] A theoretical synthesis of "Western knowledge" and "Eastern morality" would later be accomplished by Sakuma Shōzan and Yokoi Shōnan, in view of "controlling the barbarians with their own methods".[7]

After 1839, however, traditionalists tended to prevail. Students of Western sciences were accused of treason (Bansha no goku), put under house arrest (Takashima Shūhan), forced to commit ritual suicide (Watanabe Kazan, Takano Chōei), or even assassinated as in the case of Sakuma Shōzan.

-

Russians meeting Japanese in 1779

Perry Expedition (1853–54)

[edit]

When Commodore Matthew C. Perry's four-ship squadron appeared in Edo Bay (Tokyo Bay) in July 1853, the shogunate was thrown into turmoil. Commodore Perry was fully prepared for hostilities if his negotiations with the Japanese failed, and threatened to open fire if the Japanese refused to negotiate. He gave them two white flags, telling them to hoist the flags when they wished a bombardment from his fleet to cease and to surrender.[8] To demonstrate his weapons, Perry ordered his ships to attack several buildings around the harbor. The ships of Perry were equipped with new Paixhans shell guns, capable of destroying buildings by delivering explosive shells at high velocity.[9][10]

Japan's response

[edit]In response to the Perry Expedition and increasing incursions of foreign warships into Japanese territorial waters, several modern sailing frigates, including Shōhei Maru and Asahi Maru, were constructed on orders of the Tokugawa shogunate by the Satsuma Domain. The Shōhei Maru was built from 1853 to 1854 at Sakurajima in what is now Kagoshima Prefecture in accordance with a Dutch blueprint. Furthermore, fortifications were established at Odaiba in Tokyo Bay in order to protect Edo from an American incursion. Industrial developments also commenced soon afterwards in order to build modern cannons. A reverbatory furnace was established by Egawa Hidetatsu in Nirayama to cast cannons.[11]

-

Odaiba battery at the entrance of Tokyo, built in 1853–54 to prevent an American intrusion

-

Nirayama (韮山) reverberatory furnace in Izunokuni, Shizuoka built by Egawa Hidetatsu. Construction began in November 1853 and was completed in 1857; it operated until 1864.[a]

-

One of the cannons of Odaiba, now at the Yasukuni Shrine. 80-pound bronze; bore: 250 mm, length: 3830 mm.

-

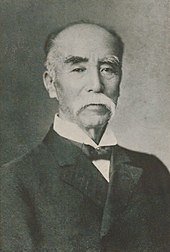

Marquess Kuroda Nagahiro of Fukuoka. Nagahiro (like his close relative, Shimazu Nariakira) was a serious proponent of technological modernization after Commodore Perry's arrival. He greatly encouraged learning amongst his retainers, and sent them to the best schools of Edo, Osaka, and Nagasaki to absorb the Western knowledge and technical expertise which was entering the country at the time.

The American fleet returned in 1854. The chairman of the senior councillors, Abe Masahiro, was responsible for dealing with the Americans. Having no precedent to manage this threat to national security, Abe tried to balance the desires of the senior councillors, who wanted to compromise with the foreigners, of the emperor, who wanted to keep the foreigners out, and of the feudal daimyō rulers, who wanted to go to war. Lacking consensus, Abe compromised by accepting Perry's demands for opening Japan to foreign trade while also making military preparations. In March 1854, the Treaty of Peace and Amity (or Treaty of Kanagawa) maintained the prohibition on trade but opened the ports of Shimoda and Hakodate to American whaling ships seeking provisions, guaranteed good treatment to shipwrecked American sailors, and allowed a United States consul to take up residence in Shimoda, a seaport on the Izu Peninsula, southwest of Edo. In February 1855, the Russians followed suit with the Treaty of Shimoda.[citation needed]

The resulting damage to the shogunate was significant. Debate over government policy was unusual and had engendered public criticism of the shogunate. In the hope of enlisting the support of new allies, Abe, to the consternation of the fudai daimyō, had consulted with the shinpan and tozama daimyō, further undermining the already weakened bakufu.

In the Ansei Reform (1854–1856), Abe then tried to strengthen the regime by ordering Dutch warships and armaments from the Netherlands and building new port defenses. In 1855, with Dutch assistance, the shogunate acquired its first steam warship, the Kankō Maru, which was used for training, and opened the Nagasaki Naval Training Center with Dutch instructors, while a Western-style military school was established at Edo. In 1857, it acquired its first screw-driven steam warship, the Kanrin Maru. Scientific knowledge grew swiftly from the existing foundation of Western learning (rangaku ("Dutch learning")).

Opposition to Abe increased within fudai circles, which opposed opening shogunate councils to the tozama daimyō, and he was replaced in 1855 as chairman of the senior councilors by Hotta Masayoshi (1810–1864). At the head of the dissident faction was Tokugawa Nariaki, who had long embraced a militant loyalty to the emperor along with anti-foreign sentiments, and who had been put in charge of national defense in 1854. The Mito school—based on neo-Confucian and Shinto principles—had as its goal the restoration of the imperial institution, and the turning back of the West.

Japanese historian Motohiko Izawa stated in his book, "The United States simply aimed to conduct business, which wasn't a bad thing for Japan. In fact, one could even say it was appealing. However, among the senior officials of the Shogunate, there was a trauma from the Nagasaki Harbour Incident. They probably adopted a hardline stance as a result of assuming that Americans were no different from the British."[12]

-

The Kanrin Maru, Japan's first screw-driven steam warship, 1855

Earthquakes

[edit]The years 1854–1855 saw a dramatic series of earthquakes, known as the Ansei great earthquakes, with 120 major and minor tremors recorded over a less than two-year period including the 8.4 magnitude 1854 Tōkai earthquake on 23 December 1854, the 8.4 magnitude 1854 Nankai earthquake occurring the following day, and the 6.9 magnitude 1855 Edo earthquake, which struck what is today modern Tokyo, on 11 November 1855. Shimoda on the Izu Peninsula was struck by the Tōkai earthquake and a subsequent tsunami, and because the port had just been designated as the prospective location for a US consulate, some construed the natural disasters as demonstration of the displeasure of the gods.[13] As the earthquakes were blamed by many Japanese on a giant catfish (Namazu) thrashing about, Ukiyo-e prints depicting namazu became very popular during this time.

-

The wreckage of Diana following the 1854 Ansei-Tōkai earthquake and tsunami, Illustrated London News, 1856

Treaties imposed upon Japan

[edit]

Following the nomination of Townsend Harris as the U.S. Consul in 1856 and two years of negotiation, the Treaty of Amity and Commerce was signed in 1858 and put into application from mid-1859. During the negotiations, Harris had convinced the Japanese negotiators to sign the treaty on the basis it was the best possible terms a Western power would offer.[14][15]

The most important points of the Treaty were:

- exchange of diplomatic agents.

- Edo, Kobe, Nagasaki, Niigata, and Yokohama's opening to foreign trade as ports.

- ability of United States citizens to live and trade at will in those ports (only opium trade was prohibited).

- a system of extraterritoriality that provided for the subjugation of foreign residents to the laws of their own consular courts instead of the Japanese law system.

- fixed low import-export duties, subject to international control

- ability for Japan to purchase American shipping and weapons (three American steamships were delivered to Japan in 1862).

Japan was also forced to apply any further conditions granted to other foreign nations in the future to the United States, under the "most favoured nation" provision. Several foreign nations soon followed suit and obtained treaties with Japan (the Ansei Five-Power Treaties, with the United States (Harris Treaty) on July 29, 1858, the Netherlands (Treaty of Amity and Commerce between the Netherlands and Japan) on August 18, Russia (Treaty of Amity and Commerce between Russia and Japan) August 19, the United Kingdom (Anglo-Japanese Treaty of Amity and Commerce) on August 26, and France (Treaty of Amity and Commerce between France and Japan) on October 9).

Trading houses were quickly set up in the open ports.

-

Map of newly opened Yokohama Port 1859–1860

-

View of Yokohama in 1859

Crisis

[edit]Collapse of the Japanese economy

[edit]| Japanese foreign trade (1860–1865, in Mexican dollars)[16] | ||

| 1860 | 1865 | |

| Exports | 4.7 million | 17 million |

| Imports | 1.66 million | 15 million |

The opening of Japan to uncontrolled foreign trade brought massive economic instability. While some prospered, many others went bankrupt. Unemployment rose, as well as inflation. Coincidentally, major famines also increased the price of food drastically. Incidents occurred between brash foreigners and the Japanese.

Japan's monetary system, based on Tokugawa coinage, also broke down. Traditionally, Japan's exchange rate between gold and silver was 1:5, whereas international rates were of the order of 1:15. This led to massive purchases of gold by foreigners, and ultimately forced the Japanese authorities to devalue their currency.[17] There was a massive outflow of gold from Japan, as foreigners rushed to exchange their silver for "token" silver Japanese coinage and again exchange these against gold, giving a 200% profit to the transaction. In 1860, about 4 million ryōs thus left Japan,[18] that is about 70 tons of gold. This effectively destroyed Japan's gold standard system, and forced it to return to weight-based system with International rates. The Bakufu instead responded to the crises by debasing the gold content of its coins by two thirds, so as to match foreign gold-silver exchange ratios.[18]

Foreigners also brought cholera to Japan, leading to hundreds of thousands of deaths.[17]

-

Foreign ships in Yokohama harbor

-

A foreign trading house in Yokohama in 1861

-

Allegory of inflation and soaring prices during the Bakumatsu era

Political and social crisis

[edit]

Hotta lost the support of key Daimyōs, and when Tokugawa Nariaki opposed the new treaty, Hotta sought imperial sanction. The court officials, perceiving the weakness of the bakufu, rejected Hotta's request, resulting in his resignation, and embroiling Kyoto and the Emperor in Japan's internal politics for the first time in centuries. When the shōgun died without an heir, Nariaki appealed to the court for support of his own son, Tokugawa Yoshinobu (or Keiki), for shōgun, a reformist candidate favored by the shinpan and tozama daimyōs. The fudai won the power struggle, however, installing the 12 year old Tokugawa Iemochi as shōgun whom it was perceived Tairō Ii Naosuke would have influence over, ultimately placing Nariaki and Yoshinobu under house arrest, and executing Yoshida Shōin (1830–1859, a leading sonnō-jōi intellectual who had opposed the American treaty and plotted a revolution against the bakufu) known as the Ansei Purge.

Tairō Ii Naosuke, who had signed the Harris Treaty and tried to eliminate opposition to Westernization with the Ansei Purge, was himself murdered in March 1860 in the Sakuradamon incident. A servant of the French Minister was attacked at the end of 1860.[19] On 14 January 1861, Henry Heusken, Secretary to the American mission, was attacked and murdered.[19] On 5 July 1861, a group of samurai attacked the British Legation, resulting in two deaths.[19] During this period, about one foreigner was killed every month. The Richardson Affair occurred in September 1862, forcing foreign nations to take decisive action in order to protect foreigners and guarantee the implementation of Treaty provisions. In May 1863, the US legation in Edo was torched.

During the 1860s, peasant uprisings and urban disturbances multiplied. A "World renewal" movement appeared, as well as religious festivals and protests such as the Eejanaika.[citation needed]

From 1859, the ports of Nagasaki, Hakodate and Yokohama became open to foreign traders as a consequence of the Treaties.[20] Foreigners arrived in Yokohama and Kanagawa in great numbers, giving rise to trouble with the samurai.[19] Violence increased against the foreigners and those who dealt with them. Murders of foreigners and collaborating Japanese soon followed. On 26 August 1859, a Russian sailor was cut to pieces in the streets of Yokohama.[19] In early 1860, two Dutch captains were slaughtered, also in Yokohama.[19] Chinese and native servants of foreigners were also killed.[19]

-

Attack on the British legation in Edo, July 1861

-

Assassination of Tairō Ii Naosuke in the Sakuradamon incident (1860)

Initial efforts to revise the imposed treaties

[edit]

Several missions were sent abroad by the Bakufu, in order to revise the commercial treaties. However, these efforts remained largely unsuccessful. A Japanese Embassy to the United States was sent in 1860, on board the Kanrin Maru and the USS Powhattan. A First Japanese Embassy to Europe was sent in 1862. A Second Japanese Embassy to Europe would be sent in December 1863, with the mission to obtain European support to reinstate Japan's former closure to foreign trade, and especially stop foreign access to the harbor of Yokohama. The Embassy ended in total failure as European powers did not see any advantages in yielding to its demands.

Sonnō Jōi (1863–66)

[edit]

Belligerent opposition to Western influence further erupted into open conflict when the Emperor Kōmei, breaking with centuries of imperial tradition, began to take an active role in matters of state and issued, on March 11 and April 11, 1863, his "Order to expel barbarians" (攘夷実行の勅命, jōi jikkō no chokumei).

The Mōri clan of Chōshū, under Lord Mōri Takachika, followed on the order, and began to take actions to expel all foreigners from the date fixed as a deadline (May 10, Lunar calendar). Openly defying the shogunate, Mōri ordered his forces to fire without warning on all foreign ships traversing Shimonoseki Strait.

Under pressure from the Emperor, the Shogun was also forced to issue a declaration promulgating the end of relations with foreigners. The order was forwarded to foreign legations by Ogasawara Zusho no Kami on June 24, 1863:

The orders of the Tycoon, received from Kyoto, are to the effect that the ports are to be closed and the foreigners driven out, because the people of the country do not desire intercourse with foreign countries.

— Missive of Ogasawara Dzusho no Kami, June 24, 1863, quoted in A Diplomat in Japan, Ernest Satow, p75

Edward Neale, the head of the British Legation, responded on very strong terms, equating the move with a declaration of war:

It is, in fact, a declaration of war by Japan itself against the whole of the Treaty Powers, and the consequences of which, if not at once arrested, it will have to expiate by the severest and most merited chastisement

— Edward Neale, June 24, 1863. Quoted in A Diplomat in Japan, Ernest Satow, p77

-

An 1861 image expressing the Jōi (攘夷, "Expel the Barbarians") sentiment

-

Japanese cannons shooting on Foreign shipping at Shimonoseki in 1863

Foreign military interventions against sonnō jōi

[edit]American influence, which had been of high importance in the beginning, waned after 1861 due to the advent of the American Civil War (1861–1865) that monopolized all available U.S. resources. This influence would be replaced by that of the British, the Dutch and the French.

The two ringleaders of the opposition to the bakufu were from the Satsuma (present day Kagoshima prefecture) and Chōshū (present-day Yamaguchi prefecture) provinces, two of the strongest tozama anti-shogunate domains in Edo-period Japan. Satsuma military leaders Saigō Takamori and Okubo Toshimichi were brought together with Katsura Kogoro of Chōshū, notably through the efforts of Sakamoto Ryōma. As the former happened to be directly involved in the murder of Richardson, and the latter in the attacks on foreign shipping in Shimonoseki, and as the bakufu declared itself unable to placate them, Allied forces decided to mount direct military expeditions.

In the morning of July 16, 1863, under sanction by Minister Pruyn, in an apparent swift response to the attack on the Pembroke, the U.S. frigate USS Wyoming under Captain McDougal sailed into the strait and single-handedly engaged the U.S.-built but poorly manned fleet. For almost two hours before withdrawing, McDougal sank one Japanese vessel and severely damaged the other two, along with some forty Japanese casualties, while the Wyoming suffered extensive damage with fourteen crew dead or wounded.

-

The USS Wyoming battling in the Shimonoseki Straits against the Choshu steam warships Daniel Webster (six guns), the brig Lanrick (Kosei, with ten guns), and the steamer Lancefield (Koshin, of four guns)

-

USS Wyoming sinking the Choshu steamer Lancefield

On the heels of McDougal's engagement, two weeks later a French landing force of two warships, the Tancrède and the Dupleix, and 250 men under Captain Benjamin Jaurès swept into Shimonoseki and destroyed a small town, together with at least one artillery emplacement.

In August 1863, the Bombardment of Kagoshima took place, in retaliation for the Namamugi incident and the murder of the English trader Richardson. The Royal Navy bombarded Kagoshima and sunk several ships. Satsuma however later negotiated and paid 25,000 pounds, but did not remit Richardson's killers, and in exchange obtained an agreement by Great Britain to supply steam warships to Satsuma. The conflict actually became the starting point of a close relationship between Satsuma and Great Britain, which became major allies in the ensuing Boshin War. From the start, the Satsuma Province had generally been in favour of the opening and modernization of Japan. Although the Namamugi Incident was seen as unfortunate, it was taken not to be characteristic of Satsuma's policy, and was instead branded as an example of anti-foreign sonnō jōi sentiment, as a justification to a strong Western show of force.

-

Birds-eye view of the bombardment of Kagoshima by the Royal Navy, August 15, 1863. Le Monde Illustré.

-

Initial settlement between the Bakufu and the British

Naval forces from Great Britain, France, the Netherlands and the United States, planned an armed reaction against Japanese acts of violence against the citizens with the Bombardment of Shimonoseki. The Allied intervention occurred in September 1864, combining the naval forces of the four nations, against the powerful daimyō Mōri Takachika of the Chōshū Domain based in Shimonoseki, Japan. This conflict proved inopportune for America,[according to whom?] which in 1864, was already torn by its own civil war.

-

The Bombardment of Shimonoseki, 1863–1864

-

The French engagement at Shimonoseki, with the warships Tancrède and Semiramis, under Rear-Admiral Charles Jaurès. Le Monde illustré, October 10, 1863.

-

French Navy troops taking possession of Japanese cannons at Shimonoseki

Following these successes against the imperial movement in Japan, the shogunate was able to reassert a certain level of primacy at the end of 1864. The traditional policy of sankin-kōtai was reinstated, and remnants of the rebellions of 1863–64 as well as the Shishi movement were brutally suppressed throughout the land.[21]

The military interventions by foreign powers also proved that Japan was no military match against the Allies. The sonnō jōi movement thus lost its initial impetus. The structural weaknesses of the Bakufu however remained an issue, and the focus of opposition would then shift to creating a strong government under a single authority.

Mito Rebellion

[edit]On 2 May 1864, the Mito rebellion erupted against the power of the shogunate in the name of the sonnō jōi. The Shogunate managed to send an army to quell the revolt, which ended with the surrender of the rebels on 14 January 1865.

First Chōshū Expedition

[edit]In the Kinmon Incident on 20 August 1864, troops from Chōshū Domain attempted to take control of Kyoto and the Imperial Palace in order to pursue the objective of Sonnō Jōi. This also led to a punitive expedition by the Tokugawa government, the First Chōshū expedition.

Hyōgo Naval Expedition

[edit]As the Bakufu proved incapable to pay the $3,000,000 indemnity demanded by foreign nations for the intervention at Shimonoseki, foreign nations agreed to reduce the amount in exchange for a ratification of the Harris Treaty by the Emperor, a lowering of customs tariffs to a uniform 5%, and the opening of the harbours of Hyōgo (modern Kōbe) and Osaka to foreign trade. In order to press their demands more forcefully, a squadron of four British, one Dutch and three French warships were sent to the harbour of Hyōgo in November 1865. Other displays of force were made by foreign forces, until the Emperor finally agreed to change his total opposition to the Treaties, by formally allowing the shōgun to handle negotiations with foreign powers. An agreements providing for the tariff revision was signed in June 1866.[22]

These conflicts led to the realization that head-on conflict with Western nations was not a solution for Japan. As the Bakufu continued its modernization efforts, Western daimyōs (especially from Satsuma and Chōshū) also continued to modernize intensively in order to build a stronger Japan and to establish a more legitimate government under Imperial power.

Second Chōshū Expedition

[edit]The shogunate led a second punitive expedition against Chōshū from June 1866, but the shogunate was defeated by the more modern and better organized troops of Chōshū. The new shōgun Tokugawa Yoshinobu managed to negotiate a ceasefire due to the death of the previous shōgun, but the prestige of the shogunate was nevertheless seriously affected.

This reversal encouraged the Bakufu to take drastic steps towards modernization.[23]

The downfall of the Tokugawa shogunate (1867–69)

[edit]

Modernization

[edit]During the last years of the bakufu, or bakumatsu, the bakufu took strong measures to try to reassert its dominance, although its involvement with modernization and foreign powers was to make it a target of anti-Western sentiment throughout the country.

Naval students were sent to study in Western naval schools for several years, starting a tradition of foreign-educated future leaders, such as Admiral Enomoto Takeaki. The French naval engineer Léonce Verny was hired to build naval arsenals, such as Yokosuka and Nagasaki. By the end of the Tokugawa shogunate in 1868, the Japanese navy of the shōgun already possessed eight western-style steam warships around the flagship Kaiyō Maru, which were used against pro-imperial forces during the Boshin War, under the command of Admiral Enomoto. A French Military Mission to Japan was established to help modernize the armies of the Bakufu. Japan sent a delegation to and participated in the 1867 World Fair in Paris.

Tokugawa Yoshinobu (informally known as Keiki) reluctantly became head of the Tokugawa house and shōgun following the unexpected death of Tokugawa Iemochi in mid-1866. In 1867, Emperor Kōmei died and was succeeded by his second son, Mutsuhito, as Emperor Meiji. Tokugawa Yoshinobu tried to reorganize the government under the Emperor while preserving the shōgun's leadership role, a system known as kōbu gattai. Fearing the growing power of the Satsuma and Chōshū daimyōs, other daimyōs called for returning the shōgun's political power to the emperor and a council of daimyōs chaired by the former Tokugawa shōgun. With the threat of an imminent Satsuma-Chōshū led military action, Yoshinobu moved pre-emptively by surrendering some of his previous authority.

Boshin War

[edit]After Keiki had temporarily avoided the growing conflict, anti-shogunal forces instigated widespread turmoil in the streets of Edo using groups of rōnin. Satsuma and Chōshū forces then moved on Kyoto in force, pressuring the Imperial Court for a conclusive edict demolishing the shogunate. Following a conference of daimyōs, the Imperial Court issued such an edict, removing the power of the shogunate in late 1867. The Satsuma, Chōshū, and other han leaders and radical courtiers, however, rebelled, seized the imperial palace, and announced their own restoration on January 3, 1868. Keiki nominally accepted the plan, retiring from the Imperial Court to Osaka at the same time as resigning as shōgun. Fearing a feigned concession of the shogunal power to consolidate power, the dispute continued until culminating in a military confrontation between Tokugawa and allied domains with Satsuma, Tosa and Chōshū forces, in Fushimi and Toba. With the turning of the battle toward anti-shogunal forces, Keiki then quit Osaka for Edo, essentially ending both the power of the Tokugawa and the shogunate that had ruled Japan for over 250 years.

Following the Boshin War (1868–1869), the bakufu was abolished, and Keiki was reduced to the ranks of the common daimyōs. Resistance continued in the North throughout 1868, and the bakufu naval forces under Admiral Enomoto Takeaki continued to hold out for another six months in Hokkaidō, where they founded the short-lived Republic of Ezo. This defiance ended in May 1869 at the Battle of Hakodate, after one month of fighting.

-

Shogunal troops in 1864, Illustrated London News

See also

[edit]Shōguns

[edit]Daimyōs

[edit]- Tokugawa Nariaki

- Ii Naosuke

- Kuroda Nagahiro

- Date Munenari

- Matsudaira Yoshinaga

- Yamauchi Toyoshige

- Shimazu Nariakira

- Hachisuka Narihiro

- Hotta Masayoshi

Matsudaira Yoshinaga, Date Munenari, Yamauchi Toyoshige and Shimazu Nariakira are collectively referred to as Bakumatsu no Shikenkō (幕末の四賢侯).

Other prominent figures

[edit]- Kawakami Gensai (greatest of 4 hitokiri, active in assassinations during this time period)

- Takano Chōei – Rangaku scholar

- Iinuma Sadakichi

Foreign observers:

- Ernest Satow in Japan 1862–69

- Edward and Henry Schnell

- Robert Bruce Van Valkenburgh, American Minister-Resident

- Matthew C. Perry

- Joel Abbot

International relations

[edit]Explanatory footnotes

[edit]- ^ A Dutch book entitled The Casting Processes at the National Iron Cannon Foundry in Luik (Het Gietwezen ins Rijks Iizer-Geschutgieterij, to Luik) written in 1826 by Huguenin Ulrich (1755–1833) was used as a reference to build the furnace.[11]

Citations

[edit]- ^ Hillsborough 2005, p. 48

- ^ Ravina 2004, p. 42

- ^ a b c Jansen 2002, p. 287

- ^ a b Kornicki 1998, p. 246

- ^ Cullen 2003, pp. 158–159

- ^ a b Jansen 1997, p. 124

- ^ Jansen 1997, pp. 126–130

- ^ Takekoshi 2004, pp. 285–86

- ^ Millis 1981, p. 88

- ^ Walworth 1946, p. 21

- ^ a b Iida 1980

- ^ 学校では教えてくれない江戸・幕末史の授業. PHP Bunko. 2021. p. 336. ISBN 978-4-569-90107-7.

- ^ Hammer 2006, p. 65

- ^ Satow 2006, p. 33

- ^ Harris, Townsend (1930). The Complete Journal of Townsend Harris, First American Consul General and Minister to Japan. Japan Society, New York.

- ^ Jansen 1997, p. 175

- ^ a b Dovwer 2008, p. 2

- ^ a b Metzler 2006, p. 15

- ^ a b c d e f g Satow 2006, p. 34

- ^ Satow 2006, p. 31

- ^ Totman 1997, pp. 140–147

- ^ Satow 2006, p. 157

- ^ Jansen 1997, p. 188

General and cited references

[edit]- Cullen, Louis M. (2003). A History of Japan, 1582–1941: Internal and External Worlds (1st ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52918-1.

- Dovwer, John W. (2008). "Chapter Two: Chaos" (PDF). Yokohama Boomtown: Foreigners in Treaty-Port Japan (1859–1872). Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Visualizing Cultures.

- Hammer, Joshua (2006). Yokohama Burning: The Deadly 1923 Earthquake and Fire That Helped Forge the Path to World War II. New York: Free Press. ISBN 978-0-7432-6465-5. OCLC 67774380.

- Hillsborough, Romulus (2005). Shinsengumi: The Shōgun's Last Samurai Corps. Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8048-3627-2.

- Iida, Ken'ichi (1980). Origin and Development of Iron and Steel Technology in Japan. HSDP-JE series/The United Nations University, Project on Technology Transfer, Transformation, and Development: The Japanese Experience (JE). Tokyo: United Nations University. ISBN 978-92-808-0089-0.

- Jansen, Marius B., ed. (1997) [1995]. The Emergence of Meiji Japan (Reprint ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-521-48405-3. OCLC 31515308.

- Jansen, Marius B. (2002). The Making of Modern Japan (1st paperback ed.). Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-00991-2.

- Kornicki, Peter Francis, ed. (1998). Meiji Japan: Political, Economic and Social History, 1868–1912. Routledge Library of Modern Japan. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-15618-9.

- Metzler, Mark (2006). Lever of Empire: The International Gold Standard and the Crisis of Liberalism in Prewar Japan. Twentieth-century Japan. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-520-24420-7. OCLC 58043070.

- Millis, Walter (1981). Arms and Men: A Study in American Military History. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-0931-0.

- Ravina, Mark (2004). The Last Samurai: The Life and Battles of Saigō Takamori. Hoboken, N.J: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 978-0-471-08970-4.

- Satow, Ernest Mason, ed. (2006). A Diplomat in Japan: The Inner History of the Critical Years in the Evolution of Japan When the Ports Were Opened and the Monarchy Restored, Recorded by a Diplomatist Who Took an Active Part in the Events of the Time, with an Account of His Personal Experiences During That Period. Yohan classics. Berkeley, Calif.: Stone Bridge Press. ISBN 978-1-933330-16-7.

- Takekoshi, Yosaburō (2004). The Economic Aspects of the History of the Civilization of Japan. Vol. 3 (Reprint ed.). London: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-32381-9.

- Totman, Conrad D. (1997). The Collapse of the Tokugawa Bakufu: 1862–1868 (Reprint ed.). Honolulu: Univ. Press of Hawaii. ISBN 978-0-8248-0614-9.

- Walworth, Arthur (1946). Black Ships Off Japan: The Story of Commodore Perry's Expedition. A. A. Knopf. ISBN 978-1-443-72850-8.

Further reading

[edit]- Arnold, Bruce Makoto (2005). Diplomacy Far Removed: A Reinterpretation of the U.S. Decision to Open Diplomatic Relations with Japan (B.A. thesis). University of Arizona.

- Denney, John W. (2011). Respect and Consideration: Britain in Japan 1853–1868 and Beyond. Leicester, UK: Radiance Press. ISBN 978-0-9568798-0-6.

- Fortune, Robert (2020). Travels in Bakumatsu Japan. Toyo Press. ISBN 978-94-92722-31-7.

- Humbert, Aimé (2019). De Lange, William (ed.). Bakumatsu Japan: Travels Through a Vanishing World. Toyo Press. ISBN 978-9492722201.

- Kitahara, Michio (Spring 1986). "Commodore Perry and the Japanese: A Study in the Dramaturgy of Power". Symbolic Interaction. 9 (1): 53–65. doi:10.1525/si.1986.9.1.53. JSTOR 10.1525/si.1986.9.1.53.

![Nirayama (韮山) reverberatory furnace in Izunokuni, Shizuoka built by Egawa Hidetatsu. Construction began in November 1853 and was completed in 1857; it operated until 1864.[a]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7c/Reverberatory_furnace_of_Nirayama.jpg/200px-Reverberatory_furnace_of_Nirayama.jpg)