Franco Luambo

Franco Luambo | |

|---|---|

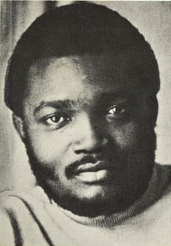

Luambo Makiadi in the early 1970s | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | François Luambo Luanzo Makiadi |

| Also known as | Franco |

| Born | 6 July 1938 Sona Bata, Belgian Congo (modern-day Democratic Republic of the Congo) |

| Origin | Sona-Bata |

| Died | 12 October 1989 (aged 51) Mont-Godinne, Province of Namur, Belgium |

| Genres | |

| Occupations |

|

| Instrument(s) | Guitar vocals |

| Years active | 1950s–1980s |

| Labels | |

| Formerly of |

|

François Luambo Luanzo Makiadi (6 July 1938 – 12 October 1989) was a Congolese singer, guitarist, songwriter, bandleader, and cultural revolutionary.[1][2][3][4] He was a central figure in 20th-century Congolese and African music, principally as the bandleader for over 30 years of TPOK Jazz, the most popular and influential African band of its time and arguably of all time.[5][6][7] He is referred to as Franco Luambo or simply Franco. Known for his mastery of African rumba, he was nicknamed by fans and critics "Sorcerer of the Guitar" and the "Grand Maître of Zairean Music", as well as Franco de Mi Amor by female fandom.[8] AllMusic described him as perhaps the "big man in African music".[9] His extensive musical repertoire was a social commentary on love, interpersonal relationships, marriage, decorum, politics, rivalries, mysticism, and commercialism.[10][11] In 2023, Rolling Stone ranked him at number 71 on its list of the 250 Greatest Guitarists of All Time.[12]

Between 1952 and 1955, Luambo made his music debut as a guitarist for Bandidu, Watam, LOPADI, and Bana Loningisa.[13] In 1956, he co-founded OK Jazz (later known as TPOK Jazz), which emerged as a defining force in Congolese and African popular music.[14][15][16] As the band's leading guitarist, he assumed sole leadership in 1970 and introduced innovations to African rumba, including altering the placement of the genre's instrumental interlude sebene at the end of songs.[17] He also developed a distinct thumb-and-forefinger plucking style to create an auditory illusion of sebene's two guitar lines and established TPOK Jazz's guitar-centric lineup, often showcasing his own mi-solo, which bridges the rhythm guitar and the lead guitar.[18][19][17]

During the 1970s, Luambo became more politically involved as president Mobutu Sese Seko promoted his state ideology of Authenticité.[20][21][22] He wrote a variety of songs that praised Mobutu's regime and other political figures.[23] In 1985, Luambo and TPOK Jazz sustained their prominence with their Congolese rumba smash hit "Mario", which sold over 200,000 copies in Zaire and achieved gold certification.[24] The BBC named him among fifty African icons.[25]

Life and career

[edit]1938–1952: Early life and career beginnings

[edit]

François Luambo Luanzo Makiadi was born on 6 July 1938 in Sona-Bata, a town located in then-Bas-Congo Province (now Kongo Central), in what was then the Belgian Congo (later the Republic of the Congo, then Zaire, and currently the Democratic Republic of the Congo).[26][27][28] He came from an interethnic background: his father, Joseph Emongo, was a Tetela railway worker, while his mother, Hélène Mbongo Makiese, was Kongo with Ngombé roots through her paternal lineage.[29][30] Luambo was one of three children from their matrimonial union, along with his siblings Siongo Bavon (alias Bavon Marie-Marie) and Marie-Louise Akangana.[31] After Joseph Emongo's death, Hélène had three more children with two other partners: Alphonse Derek Malolo, Marie Jeanne Nyantsa, and Jules Kinzonzi.[31]

Luambo was raised in Léopoldville (presently Kinshasa) on Opala Avenue, within the district of Dendale (modern-day Kasa-Vubu commune). He matriculated at Léo II primary school in Kintambo.[31] By 1948, he became increasingly enamored with music, inspired by the emerging Congolese rumba scene, mainly through musicians like Joseph Athanase Tshamala Kabasele (colloquially known as Le Grand Kallé).[31] Luambo started out by playing the harmonica. In 1949, at the age of 11, he experienced the loss of his father, which effectively curtailed his formal education due to financial constraints.[31] With no alternative to continue his schooling, he began devoting his time to playing the harmonica and other instruments and later joined a group called Kebo, noted for its rhythmic sound, primarily produced by patenge, a wooden frame drum held between the legs, with its tone altered by pressing the skin with the heel.[31] As financial hardships exacerbated, Luambo's mother, apprehensive about his future, sought assistance from a family acquaintance, Daniel Bandeke. Bandeke secured Luambo a job packing records at a well-known record label and studio named Ngoma.[31] There, entranced by the musicians he met, he clandestinely taught himself to play guitar whenever the musicians finished their recordings. According to Congolese musicologist Clément Ossinondé, Luambo's ability quickly became apparent, with immense astonishment prevailing "the day it was discovered that the packer was a budding guitar genius".[31]

In 1950, the family relocated from Opala Avenue to Bosenge Street in Ngiri-Ngiri. They rented a house owned by the family of the famed Congolese musician Paul Ebengo Dewayon, who had a homemade guitar and was progressing significantly as a guitarist.[32] Luambo and Dewayon struck up a friendship, which allowed him to develop his skills further. Another notable mentor was Albert Luampasi, a guitarist and composer affiliated with Ngoma.[32] Under Luampasi's tutelage, Luambo further polished his guitar skills. He was then included in Luampasi's fold alongside Paul, and they began attending performances with his band, Bandidu.[32] Although, at that time, musical pursuits were viewed as degrading and synonymous with delinquency for those who engaged in them, Luambo pursued it with immense zeal to assist his mother, whose sole source of sustenance for the entire family came from Mama Makiese's operation of a doughnut stall at the Ngiri-Ngiri market colloquially known as wenze ya bayaka.[32][33] In 1952, Luambo officially joined Bandidu and toured with the group in Bas-Congo, including an extended stay in Moerbeke, Kwilu Ngongo, where they remained for several months.[32] By that juncture, Albert Luampasi had already released four tracks with Ngoma, which enabled Luambo to forge a strong reputation.[32] Tracks such as "Chérie Mabanza", "Nzola Andambo", "Ziunga Kia Tumba", and "Mu Kintwadi Kieto" became emblematic of this period.[32] He also became associated with the Bills subculture during this period.[34]

1953: Watam

[edit]Luambo's period with the Léopoldville-based band Watam remains a subject of contentious debate, with differing accounts concerning the formation and his participation in the band. British musicologist Gary Stewart suggests that Luambo, in conjunction with Paul Ebengo Dewayon, co-founded Watam in 1950, accompanied by novice musicians Louis Bikunda, Ganga Mongwalu, and Mutombo.[35]: 53 According to this account, the group played sporadic gigs over the next three years, earning small rewards for their efforts.[35]: 53 Conversely, Clément Ossinondé presents an alternative viewpoint, asserting that Watam was initially established by Paul Ebengo Dewayon, with Luambo joining the collective in 1953 after returning to Léopoldville.[32][36] That same year, Watam garnered critical acclaim with the release of two songs composed by Paul: "Bokilo Ayébi Kobota" and "Nyekesse", released on 5 February 1953 through Loningisa record label and studio.[32] The group regularly performed in the Ngiri-Ngiri commune, particularly at Kanza Bar on Rue de Bosenge, where they captivated local audiences.[32]

Regardless of the precise chronology, Luambo and Paul soon auditioned for Henri Bowane.[35]: 54 [32] Bowane then introduced Luambo to Greek producer and record executive Basile Papadimitriou at Loningisa studio on 9 August 1953.[32] Impressed by Luambo's virtuosity during the audition, Papadimitriou quickly signed him to a 10-year production contract.[32] As a token of recognition for his burgeoning abilities, Luambo was gifted a modern guitar nicknamed Libaku ya nguma ("the head of the boa") due to its considerable size.[37][38][32] It became Luambo's foremost professional guitar, which he played during studio sessions alongside Paul and Watam, rehearsing and recording tracks that met the studio's stringent criteria.[32] After the original Loningisa studio in Foncobel was deemed inadequate, Papadimitriou temporarily relocated operations to the city while constructing a new, luxurious studio in Limete, a burgeoning area south of the airport in Léopoldville.[39] Limete's strategic location on Boulevard Léopold III (now Boulevard Lumumba) allowed easy access to the band's recording activities.[39] Throughout 1953, Watam produced several notable recordings, including "Esengo Ya Mokili", "Tuba Mbote", "Bikunda", and "Groupe Watam", all written by Paul.[32] In November 1953, Luambo recorded his debut tracks with Watam at Loningisa, under the name Lwambo François: "Lilima Dis Cherie Wa Ngai" and "Kombo Ya Loningisa".[32] He continued collaborating with Watam, contributing to subsequent compositions such as "Yembele Yembele" and "Tango Ya Pokwa", which debuted on 16 December.[32] He also participated in the recording of songs composed by fellow Watam members, including Mutombo's singles "Tongo Etani Matata" and "Tika Kobola Tolo", released on 17 December.[32]

1954–1961: Rise with LOPADI and OK Jazz

[edit]In 1954, Luambo joined the LOPADI (Loningisa de Papadimitriou), a band operating under the "Loningisa" banner, led by Bowane, who gave him the epithet "Franco" that subsequently metamorphosed into his professional stage name.[32][35]: 52 He collaborated with fellow musicians such as Philippe Lando Rossignol, Daniel Loubelo "De la lune", Edo Nganga, and Bosuma Dessouin, quickly standing out with his signature guitar technique and musical inventiveness.[32][40] His debut solo recordings, "Marie Catho" and "Bayini Ngai Mpo Na Yo" (alternatively titled "Bolingo Na Ngai Na Béatrice"), premiered on 14 October 1955 and swiftly gained widespread attention, earning him the affectionate sobriquet "Franco de Mi Amor" from an expanding female fandom.[32][41] The records were acclaimed as the year's crowning achievement. The fiercely competitive scene of the mid-1950s, particularly the rivalry between the Ngoma and Opika, afforded LOPADI a platform to promote its artists.[32] Under Bowane's guidance, the band prioritized the cultivation of its musicians, with Franco standing out due to his original take on harmony and rhythm, allowing him to cultivate distinctive sound subtleties that resonated with audiences and set him apart from his contemporaries.[32]

During the latter part of 1955, Franco was part of Bana Loningisa ("children of Loningisa"), a loosely organized coalition of Léopoldville musicians that commenced collaborative efforts under the auspices of Loningisa.[35]: 56–59 [42] On 6 June 1956, at the bar-dancing venue "Home de Mulâtre", several musicians from Bana Loningisa, engaged by Oscar Kassien—who had become well-acquainted with performing at the O.K. Bar dance hall (named in tribute to its owner, Oskar Kassien)—every Saturday evening and Sunday afternoon, concurrently with their weekday commitments at the studio, thus formed an orchestra that adopted the name "OK Jazz".[32][43][44] The idea was conceived by Jean Serge Essous, who had found a better way to honor Oscar Kassien (later to become Kashama) for his laudable initiative in providing the group with instruments and the venue where it commenced.[35]: 56–59 [32] The newly established band, under the guidance of Oscar Kashama Kassien, initially had around ten musicians: Franco, Essous, Daniel Loubelo "De la lune", Philippe Lando Rossignol, Ben Saturnin Pandi, Moniania "Roitelet", Marie-Isidore Diaboua "Lièvre", Liberlin de Soriba Diop, Pella "Lamontha", Bosuma Dessoin, before ultimately consolidating to seven for the solemn outing that took place on 20 June 1956 at Parc de Boeck (now Jardin Botanique de Kinshasa).[32] While clarinetist Jean Serge Essous became the band's chief (chef d'orchestre), Franco emerged as a prolific songwriter; Essous called him a "kind of genius" for having written over a hundred songs in his notebooks then.[35]: 56–59 [42]

Franco also became known for his mastery of the "sixth" technique, wherein he plucked multiple strings at once, a style from which he gave birth to what became known as the "OK Jazz School".[32] This technique was central to the band's signature sound, which drew heavily from rumba odemba, a rhythmic and stylistic approach said to have roots in the folklore of the Mongo ethnic group from Mbandaka.[32] Social anthropologist Bob W. White characterizes rumba odemba as rhythmic, repetitive, visceral, and traditionalist.[45] The style often featured three interweaving guitars, a six-person vocal section, a seven-piece horn section, bass guitar, a drummer, and a conga player.[46] All was led by Franco on guitar and part-time lead vocals.[46] O.K. Jazz quickly became a rival to the leading established local band of that time, African Jazz under Le Grand Kallé, with Franco rivaling premier Congolese guitarists Emmanuel Tshilumba wa Boloji "Tino Baroza" and Nico Kasanda.[32] He collaborated closely with Jean Serge Essous, creating a dynamic partnership that yielded some of the band's most revered tracks, including Franco's written Congolese rumba-infused breakout anthem "On Entre O.K., On Sort K.O.", released in December 1956 by the new (and ephemeral) lineup of O.K. Jazz following personnel alterations. "On Entre O.K., On Sort K.O." achieved considerable success and evolved into the band's emblematic motto.[32][35]: 56–59 [42]

On 28 December 1956, O.K. Jazz began to see changes in its lineup. New musicians, including Edouard Ganga "Edo", Célestin Kouka, Nino Malapet (previously of the disbanded Negro Jazz orchestra), and Antoine Armando "Brazzos", were integrated into the band on 31 December, filling the void left by departing members.[32] By 1957, O.K. Jazz lost its leader, Essous, as well as original vocalist Philippe "Rossignol" Lando, when they were hired away by Bowane for his new record label, Esengo (Bowane had departed from Loningisa after O.K. Jazz eclipsed his influence).[35]: 64–65 While vocalist Vicky Longomba became the band's new leader, Franco also stepped up as the band's primary guitarist and overseer of musical direction.[35]: 64–65 [32] By then, Franco had garnered a large nationwide female fandom. In a 1957 ACP Bulletins article, Congolese Information Minister Jean Jacques Kande remarked, "In the most frequented bars in the city, he pinches his guitar, many young girls stir in his direction in tribute to their rooted damn and gratify the looks that would derail a train launched at full speed. Because Franco is an undeniable and undisputed master of the guitar...".[40] In 1958 after O.K. Jazz returned to Léopoldville after a year in Brazzaville, Franco was arrested and jailed for a "motoring offence".[47]: 188 Upon his release, he regained and reinforced his local reputation as the "Sorcerer of the Guitar".[47]: 188 His guitar technique was so influential that by the end of the 1950s and for years afterward, Congolese guitarists aligned themselves with one of two styles: the "OK Jazz School" led by Franco and the "African Jazz School" headed by Nico Kasanda of Le Grand Kallé's African Jazz.[47]: 188

In 1960, he ended his contract with Loningisa, and two years later, the Loningisa label ceased operations.[32] In 1961, O.K. Jazz became the second Congolese band to tour Brussels, following African Jazz's 1960 visit. They were subsequently invited to record in Brussels under the Surboum label, owned by Le Grand Kallé.[32] O.K. Jazz recorded several hit tracks, including "La Mode Ya Puis", "Amida Muziki Ya OK", "Nabanzi Zozo", "Jalousie Ya Nini Na Ngai", and "Como quere", among others.[32] Le Grand Kallé used the proceeds from band's recordings distributed by Surboum to procure the band's first set of musical instruments. Inspired by Le Grand Kallé after the tour that year, Franco established his own label and publishing house, Epanza Makita, with political support from Thomas Kanza, who facilitated favorable dealings with the Belgian record company Fonior.[32] This allowed him to manage his music production and distribution while still releasing records with Loningisa until it shut down the following year.[32]

1962–1989: Later years and legacy

[edit]Some people think they hear a Latin sound in our music… It only comes from the instrumentation, trumpets and so on. Maybe they are thinking of the horns. But the horns only play the vocal parts in our natural singing style. The melody follows the tonality of Lingala, the guitar parts are African and so is the rumba rhythm. Where is the Latin? Zairian music does not copy Cuban music. Some Cubans say it does, but we say their music follows ours. You know, our people went from Congo to Cuba long before we ever heard their music.

In August 1962, Ganga Edo and Loubelo "De la lune" rejoined OK Jazz.[32] Through the 1960s, Franco and O.K. Jazz "toured regularly and recorded prolifically".[47]: 188 In 1967, Franco became co-leader of O.K. Jazz alongside Vicky.[48] When Vicky left in 1970, Franco became the band's sole leader.[48] OK Jazz was rebranded as Tout Puissant O.K. Jazz (T.P.O.K. Jazz), which stands in French for "The Almighty O.K. Jazz".[49] Around this period, Franco's younger brother, Bavon Marie-Marie, died.[50] In response, Franco composed the Kikongo ballad "Kinsiona" ("Sorrow") in his honor.[50] However, rumors began to circulate, alleging that Franco had engaged in sacrificial rites involving his brother (like other parts of Africa, Kinshasa was rife with witchcraft accusations, especially against public figures such as Franco).[50] In 1973, TPOK Jazz made their first appearance in Tanzania, where an overly excited crowd caused a crowd crush, tragically killing two people who were trampled in the chaos.[51][52]

In 1978, Franco faced imprisonment for six months due to the obscene nature of his songs "Hélène" and "Jackie", which featured explicit content.[32][53] Despite this setback, Franco was released two months later following public protests and was honored by Mobutu Sese Seko for his musical contributions, although his reputation had been marred.[47]: 189 [32] In the early 1980s, TPOK Jazz was split into two factions—one based in Kinshasa and the other in Brussels—before settling in Belgium in 1982.[32] Franco and TPOK Jazz embarked on extensive tours throughout Europe and the United States, amassing significant attention. Among their prominent performances was a notable appearance at the Lisner Auditorium in Washington, D.C., in November 1983,[54] followed by another at New York's Manhattan Center in December 1983.[55][56][49] During the latter, TPOK Jazz alternated sets with and without Franco; when he performed, the music "snapped to attention; he plucked out guitar chords with a raspy, slightly distorted tone that cut the music's sweetness and sharpened its syncopations".[55] The New York Times remarked that his guitar and horn arrangements appeared "less Western than ever as they ricocheted through the music".[55] The band delivered another standout performance at Hammersmith Palais in London on 23 April 1984,[57][58] followed by three consecutive nights at Kilimanjaro's Heritage Hall in Washington, D.C., on 4 November.[59][60]

In 1985, TPOK Jazz released the Congolese rumba-infused album Mario, which experienced instant success, with the Franco-written title track earning gold certification after selling over 200,000 copies in Zaire.[61][62] The song turned into one of Luambo's most significant hits.[63] That year, they performed again at the Manhattan Center, with a lineup of 16 singers, guitarists, drummers, conga players, horn players, and six dancers.[56][64][65] In 1986, Malage de Lugendo, a vocalist, was brought into the band, as well as Kiesse Diambu ya Ntessa from Afrisa International and female vocalist Jolie Detta.[66] TPOK Jazz released the four-track long play Le Grand Maitre Franco et son Tout Puissant O.K. Jazz et Jolie Detta, featuring Franco's breakout track "Massu", Thierry Mantuika's "Cherie Okamuisi Ngai", Franco's "Layile", and Djodjo Ikomo's "Likambo Ya Somo Lumbe", featuring guest appearances from Simaro Lutumba and vocals from Jolie Detta and Malage de Lugendo.[67][68][69] The LP synthesized Congolese rumba and soukous, garnering substantial acclaim, with "Massu" and "Layile" being hailed as some of the most memorable tracks in TPOK Jazz's discography.[70][71][72] The same year, Franco and TPOK Jazz went on an extensive tour of Kenya, performing in various cities, including Eldoret and Kisumu.[73]

On 9 May 1987, Franco and TPOK Jazz performed at the Africa Mama festival in Utrecht, Netherlands, which attracted a considerable audience.[32] The concert featured an extensive lineup of 28 musicians, comprising seven singers, three dancers, eight guitarists, three trumpeters, three saxophonists, and percussionists.[74][32] The performance was immortalized in a recording, subsequently released as an album titled Franco: Still Alive, produced by former TPOK Jazz member Joseph Nganga and distributed internationally by Koch International.[74] In August 1987, Franco and TPOK Jazz played at the fourth edition of the All-Africa Games at a sold-out Moi International Sports Centre in Nairobi, headlining alongside Zaïko Langa Langa, Anna Mwale, and Jermaine Jackson.[73]

In September 1987, he collaborated with singers Nana and Baniel for a stylistic project that, although ephemeral, yielded two records that encapsulated the essence of Kinshasa's urban life.[32] Notable tracks from this epoch included "C'est dur", "Je vis comme un PDG", "Les ont dit", "La vie d'une femme célibataire", and "Flora est une femme difficile".[32] Franco's long-standing collaborator, Vicky, passed away on 12 March 1988, leaving only Franco and Bosuma Dessoin as the original band's co-founders. By September 1989, Franco's health started to decline significantly, yet he continued to perform in Brussels, London, and Amsterdam, where he played on 22 September and was later admitted to the hospital the next day.[32] Franco's final recording took place in Brussels in February 1989, contributing to Sam Mangwana's four-track album Forever, alongside session musicians and select TPOK Jazz members.[75][24] Franco's vocals and guitar feature on the hopeful opening track, "Toujours O.K.", while his guitar work also surfaces in the closing moments of a second track, "Chérie B.B."[75] He similarly played a subdued role on his own album Franco Joue avec Sam Mangwana, recorded with TPOK Jazz, where his impassioned vocals enliven the track "Lukoki", a song rooted in folklore, reminiscent of Zimbabwe's chimurenga music.[75]

Politics

[edit]Early political Involvement

[edit]Before aligning with Mobutu Sese Seko in the 1970s, Franco was an ardent proponent of the then-Republic of the Congo's inaugural prime minister, Patrice Lumumba, whose assassination was orchestrated in a clandestine operation involving the CIA, Belgian authorities, and Mobutu.[76][77][78] At the time, Mobutu, then a Chief of Staff of the Congolese National Army (Armée Nationale Congolaise; ANC), had served as Lumumba's personal aide before executing a perfidious betrayal.[79][80] Following Lumumba's assassination, Franco composed the song "Liwa ya Lumumba" ("the death of Lumumba"), alternatively titled "Liwa Ya Emery".[81][82][83] Franco then released the album Au Commandement (which translates "To authority"), wherein the eponymous track celebrated Mobutu's ascent to power. It conveyed a hopeful sentiment, praising Lumumba while portraying Mobutu as a reincarnation of Lumumba's legacy.[81]

In 1965, Mobutu seized power through a military coup, having initially pledged to relinquish control to a democratically elected government.[79] However, it soon became clear that Mobutu had no intention of stepping down, and discontent swelled, particularly in Kinshasa.[79] In a show of force, Mobutu orchestrated the public execution of five political dissidents, including Évariste Kimba and former ministers Jérôme Anany, Emmanuel Bamba, and André Mahamba, on Pentecost in Matonge.[84][85][86] The event was particularly significant as Mobutu, a Catholic, executed Bamba, a prominent Kimbanguist, a member of a traditional Kongolese religious movement.[81] In response, Franco composed the 1966 threnody "Luvumbu Ndoki" ("Luvumbu the Sorcerer"), which drew on Kikongo folklore to indirectly criticize Mobutu's regime.[81] The song's Kikongo chants, interpreted as veiled critiques of Mobutu, led to its immediate ban, with copies confiscated from the marketplace.[81] Franco was subsequently detained by Mobutu's secret police but was eventually released, after which he fled to Brazzaville to escape further persecution.[81] Despite the ban, "Luvumbu Ndoki" became emblematic of the growing frustrations of the Congolese people under Mobutu's dictatorship, and the song was re-released by EMI-Pathé in 1967.[81]

Authenticité

[edit]By the late 1960s, Mobutu started a cultural revolution to eradicate colonial legacies from Zairean society.[81] In 1971, he renamed the country from Congo-Kinshasa to Zaire.[87] He then propagated a forceful nationalist state ideology known as Authenticité, which sought to reappropriate and exalt indigenous culture while systematically eradicating colonial influence with a distinctly Zairean identity.[81][88][89][90] Even Franco altered his name to L'Okanga La Ndju Pene Luambo Luanzo Makiadi, and his music became an essential medium for disseminating Mobutu's political ideology, transforming him into a cultural icon and an advocate for the regime's agenda.[8][91][45][92] To commemorate Authenticité, Franco composed the song "Oya" ("Identity"), in which he urged Zaireans to embrace their true heritage.[81]

To promote this nationalist message, Mobutu enlisted Franco and TPOK Jazz, on a nationwide propaganda tour.[81] Clad in military fatigues, the band performed ideological hymns to massive crowds across the country.[81] His 1970 song "République du Zaire", written by Munsi Jean (Kwamy), endorsed Mobutu's renaming of the country, urging Zaireans to adopt the new national identity.[88] An album sung by TPOK Jazz was released, titled Belela Authenticité Na Congress ya M.P.R. ("acclaim authenticité of the MPR congress"), with its title track praising the concept of Authenticité, calling on the population to embrace Mobutu's cultural renaissance.[81][88] The title track also echoed the nationalist sentiments of the era, supporting Mobutu's claims to leadership and positioning him as the "head of the family"—a metaphor Mobutu used to describe his role as the unifying figure of Zaire.[88]

During this period, Franco portrayed himself as an observer of the nation's politics. In an interview, he articulated that while his lyrics touched upon political themes, he did not consider himself a politician but rather a musician reflecting the nation's realities.[88] However, Franco's close association with Mobutu's regime belied this ostensibly neutral stance.[81] He composed additional songs in support of Mobutu's policies, including "Cinq Ans Ekoki" ("five years have passed"), to commemorate Mobutu's fifth year in power.[81] When Mobutu introduced the concept of Salongo (mandatory civic labor), Franco produced a song bearing the same name to promote the initiative. During this period, Franco and TPOK Jazz performed regularly at Un-Deux-Trois Nightclub in Matonge, built on land gifted to Franco by Mobutu.[53] The club, which opened in 1974, became one of the most exclusive venues in Kinshasa. Mobutu's policies of nationalizing foreign-owned companies extended to Franco as well, as he was granted control of Mazadis, a record-pressing company, to the dismay of smaller producers and musicians who accused Franco of monopolizing access to the facility.[53] TPOK Jazz also performed at numerous political events, most notably the Zaire 74 music festival, which was organized to promote the heavyweight boxing match between Muhammad Ali and George Foreman in Kinshasa. This event highlighted Zaire's international status, and Franco performed alongside international artists like Miriam Makeba, James Brown, Etta James, Fania All-Stars, Bill Withers, The J.B.'s, B. B. King, Sister Sledge, and The Spinners, among others.[93][94][95] In 1975, Franco released the album Dixième Anniversaire to commemorate Mobutu's decade in power, though he insisted his actions were driven by civic and patriotic duty rather than political interests.[53] The reality, however, is that Franco had inevitably become entangled in the political sphere, given the era's mandate that musicians align with government directives.[53]

Imprisonment and redemption

[edit]In 1978, Franco released controversial tracks "Hélène" and "Jackie" on cassette, which authorities deemed politically and morally subversive for containing explicit content.[53][47]: 189 Summoned by Attorney General Léon Kengo wa Dondo, Franco defended the songs, claiming they contained nothing inappropriate.[53] Authorities even called upon his mother, Mbonga Makiesse, for further scrutiny, much to Franco's dismay.[53] After listening to the songs, his mother reportedly reacted with shock, and Franco was sentenced to six months' imprisonment.[53] Ten of his musicians, many unrelated to the controversial content, were also sentenced to two months, including Papa Noël Nedule, Simaro Lutumba, Kapitena Kasongo, Gerry Dialungana, Flavien Makabi, Gégé Mangaya, Makonko Kindudi (popularly known as "Makos"), Isaac Musekiwa and Lola Checain.[53] Franco attempted to take sole responsibility but was unsuccessful.[53] Despite this brief incarceration, Franco's rapport with Mobutu's regime remained intact, and later that year, Mobutu honored Franco for his contributions to Zairean culture.[47]: 188

Franco's involvement in Mobutu's political propaganda became even more pronounced in the 1980s. In 1983, he collaborated with Tabu Ley Rochereau to release a series of albums, the most famous being Lettre A Monsieur Le Directeur Général (popularly known as "D.G"), with the title track sharply criticizing the corrupt and inept bureaucrats in charge of Zaire's ministries and parastatals.[53] Although ostensibly directed at lower-level officials, many perceived the song as an implicit critique of Mobutu himself, as he had appointed these very figures.[53] Despite this, Franco continued to support Mobutu publicly, composing "Candidat Na Biso Mobutu" ("our candidate Mobutu") in 1984 to endorse the president's re-election bid, in which Mobutu ran unopposed.[96][97] The lyrics implored the public to rally behind Mobutu's leadership, extolling his governance while ominously warning against dissent, metaphorically referring to Mobutu's opponents as "sorcerers".[98][99] The song became immensely popular, earning Franco a gold disc for selling over a million copies.[100][101] However, despite this apparent camaraderie, Franco's relationship with the regime soured in the later years. The precise causes of this rift remain unclear, but it is believed that Franco's increasing influence, coupled with Mobutu's growing paranoia, may have contributed to the tension.[102][103][104][105]

Illness and death

[edit]In early 1987, Franco recorded what many consider one of his most powerful songs, "Attention Na Sida" (Beware of AIDS).[106] Sung predominantly in French to reach a broad audience, "Attention Na Sida" diverged significantly from his usual themes.[106] With its haunting guitar harmonies and intense drumming, Franco delivered a passionate and almost prophetic plea, urging people to be cautious in their intimate relationships and calling on governments to take more decisive action in the fight against AIDS.[106] At the onset of 1988, he went to Brussels for medical tests to diagnose his worsening health.[30] He had lost weight, and rumors about his illness abounded.[30] In Kinshasa, reports of Franco's death surfaced, citing possible causes like bone cancer, kidney failure, and the most controversial—AIDS.[30] In response to rumors, Franco recorded "Les Rumeurs" and two other songs in Brussels in November 1988.[75] This session was reissued as a compact disc in 1994 by SonoDisc.[75] He also contributed his final recording on Sam Mangwana's album Forever with TPOK Jazz in Brussels in February 1989.[75] However, his condition continued to decline, and he was admitted to Mont-Godinne Hospital (now CHU UCLouvain Namur).[30]

On 12 October 1989, Franco died in Namur, Belgium.[107][32] His death followed months of speculation about the illness that had been gradually consuming him, widely reported to be AIDS, though he never publicly admitted having it.[32][42] While many sources flatly report this as the cause of death, others remain uncertain, such as The New Yorker, which mentions it as "an illness believed to be AIDS".[108][109][110] Franco's body was repatriated to Kinshasa on 15 October.[32] President Mobutu declared four days of national mourning.[49][111][112] He was laid to rest in Gombe Cemetery (Cimetière de la Gombe), typically reserved for national heroes.[32] A major avenue in Kinshasa was renamed Avenue Luambo Makiadi Franco in his honor, formerly known as Avenue Bokassa.[32]

Recorded output

[edit]It is difficult to summarize the enormous volume of recordings issued by Franco (virtually all of them with TPOK Jazz), and work remains to be done in this area. The range of estimates suggest both the size of, and the uncertainties about, his output. An often-cited number is that Graeme Ewens listed eighty-four albums in the thoroughly researched discography (based on the work of Ronnie Graham) in Ewens' 1994 biography of Franco; this list does not include compilation albums that also have other performers, or O.K. Jazz tribute albums and compilations issued after Franco's death (Ewens noted about this number that "it falls short of the 150 albums which Franco claimed back in the mid-1980s, but no doubt some of those were collections of singles for the African market"). Ten albums on the list were issued in 1983 alone.[113] Other statements include: "he released roughly 150 albums and three thousand songs, of which Franco himself wrote about one thousand;"[114] "Franco’s prolific output amounted to T.P.O.K releasing two songs a week over his nearly 40-year career, which ultimately comprised a catalogue of some 1000 songs;"[46] "With his band OK Jazz he released at least 400 singles (more than half later compiled onto LP or CD) . . . . Ewens list 36 CDs; Asahi-net has 83;"[115] and "from June 1956 to August 1961 the band recorded 320 tracks for the 78 rpm music label Loningisa".[116]

As a rough explanation of its nature, in the 1950s and 1960s Franco and TPOK Jazz issued singles, either 78rpm (1950s) or 45rpm (1960s), as well as some albums that were compilations of singles, and in the 1970s and 1980s they issued longer albums. All of this was done by a large number of record labels, in a variety of countries in Africa and Europe as well as the United States. In the 1990s, many of the albums were reissued in CD form by various record labels but haphazardly reorganized, often combining various parts of multiple albums onto single CDs.[citation needed] Since 2000, several compilations have been issued collecting aspects of Franco's work, most notably Francophonic, a pair of two-CD sets of highlights issued by Stern's in 2007 and 2009 and spanning Franco's entire career. Through 2020, the Planet Ilunga record label is still able to issue (on vinyl and digitally) compilations that include tracks which had never been reissued since their original release as singles.[117]

Musical style, critical evaluations, and significance

[edit]

Franco's guitar playing was unlike that of bluesmen such as Muddy Waters or rock and rollers like Chuck Berry. Instead of raw, single-note lines, Franco built his band's style around crisp open chords, often of only two notes, which "bounced around the beat". Major thirds and sixths and other consonant intervals are said to play the same role in Franco's style that blues notes fill in rock and roll.[118]

Franco's music often relied on huge ensembles, with as many as six vocalists and several guitarists. According to a description, "horns might engage in an upbeat dialogue with the guitar, or set up hypnotic vamps that carried the song forward as on the crest of a wave", while percussion parts are "a cushion supporting the band, rather than a prod to raise the energy level".[118]

Franco was a member for 33 years, from its founding in 1956 until his death in 1989, of TPOK Jazz, which has been called "arguably the most influential African band of the second half of the 20th century".[119] and he was its co-leader or sole leader for most of that period.

Franco is commonly described as the preeminent African musical figure of the 20th century. For example, world-music expert Alistair Johnston calls him "the giant of 20th century African music".[120] A reviewer in The Guardian wrote that Franco "was widely recognized as the continent's greatest musician, back in the years before Ali Farka Touré or Toumani Diabaté".[121] Ronnie Graham wrote, in his encyclopedic 1988 Da Capo Guide to Contemporary African Music, that "Franco is beyond doubt Africa's most popular and influential musician".[47]: 188 This is in addition to listing Franco first in his book's rank-ordered section on Congo and Zaire, and putting on the book's cover, to represent African music, a waist-up photo of Franco playing guitar.

Personal life

[edit]Franco was married twice.[48] He reportedly fathered eighteen children (seventeen of them girls) with fourteen women.[8]

Selected discography

[edit]This is a very preliminary, partial list.

| Year | Album |

|---|---|

| 1969 | Franco & Orchestre O.K. Jazz* – L'Afrique Danse No. 6 (LP) |

| 1973 | Franco & OK Jazz* – Franco & L'O.K. Jazz |

| 1974 | Franco Et L'Orchestre T.P.O.K. Jazz* – Untitled |

| 1977 | "Franco" Luambo Makiadi* And His O.K. Jazz* – Live Recording of the Afro European Tour Volume 2 (LP, album) |

| 1977 | "Franco" Luambo Makiadi* & His O.K Jazz* – Live Recording of the Afro European Tour |

| 1981 | Soki Odefi Zongisa (LP, album) |

| 1982 | Franco Et Sam Mangwana Avec Le T.P. O.K. Jazz* – Franco Et Sam Mangwana Avec Le T.P.O.K. Jazz (LP) |

| 1983 | Franco & Tabu Ley* – Choc Choc Choc 1983 De Bruxelles A Paris |

| 1986 | Franco & Le T.P.O.K. Jazz – Choc Choc Choc La Vie Des Hommes – Ida – Celio (30 Ans De Carrière – 6 Juin 1956 – 6 Juin 1986) (LP) |

| 1987 | Franco Et Le T.P.O.K. Jazz – L'Animation Non Stop (LP) |

| 1988 | Le Grand Maitre Franco* - Baniel - Nana et le T.P.O.K. Jazz* - Les "On Dit" (LP) |

| 1989 | Franco Et Sam Mangwana – For Ever (LP, Cass) |

Compilation albums:

| Year | Album |

|---|---|

| 1993 | Franco & son T.P.O.K. Jazz – 3eme Anniversaire de la Mort du Grand Maitre Yorgho (CD) |

| 2001 | Franco – The Rough Guide To Franco: Africa's Legendary Guitar Maestro (CD) |

| 2007 | Franco & le T.P.O.K. Jazz – Francophonic: A Retrospective Vol. 1 1953-1980 (2 CDs) |

| 2009 | Franco & le T.P.O.K. Jazz – Francophonic: A Retrospective, Vol. 2: 1980-1989 (2 CDs) |

| 2017 | O.K. Jazz – The Loningisa Years 1956-1961 (2 records, and digital) |

| 2020 | Franco & l'Orchestre O.K. Jazz – La Rumba de mi Vida (2 records, and digital) |

| 2020 | O.K. Jazz – Pas Un Pas Sans… The Boleros of O.K. Jazz 1957-77 (2 records, and digital) |

See also

[edit]- TPOK Jazz

- Music of the Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Congolese rumba

- Soukous

- List of African musicians

References

[edit]- ^ Erenberg, Lewis A. (14 September 2021). The Rumble in the Jungle: Muhammad Ali and George Foreman on the Global Stage. Chicago, Illinois, United States: University of Chicago Press. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-226-79234-7.

- ^ Coelho, Victor, ed. (10 July 2003). The Cambridge Companion to the Guitar. Cambridge, England, United States: Cambridge University Press. pp. 57–58. ISBN 978-0-521-00040-6.

- ^ Delmas, Adrien; Bonacci, Giulia; Argyriadis, Kali, eds. (1 November 2020). Cuba and Africa, 1959-1994: Writing an alternative Atlantic history. Johannesburg, Gauteng, South Africa: Wits University Press. p. 165. ISBN 978-1-77614-633-8.

- ^ Grice, Carter (1 November 2011). ""Happy are those who sing and dance": Mobuto, Franco, and the struggle for Zairian identity". University of North Carolina Greensboro. Greensboro, North Carolina, United States. Retrieved 9 October 2024.

- ^ Stewart, Gary (June 1992). Breakout: Profiles in African Rhythm. Chicago, Illinois, United States: University of Chicago Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-226-77406-0.

- ^ Mukalo, Shem. "The Legend of The Grand Maitre: How Franco Revolutionised African Music". The Standard. Nairobi, Kenya. Retrieved 9 October 2024.

- ^ Eyre, Banning (21 March 2013). "Looking Back on Franco". Afropop Worldwide. New York, New York, United States. Retrieved 9 October 2024.

- ^ a b c Christgau, Robert (3 July 2001). "Franco de Mi Amor". Village Voice. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- ^ Nickson, Chris. "AllMusic: Franco". AllMusic. Ann Arbor, Michigan, United States. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ Ngaira, Amos (5 October 2024). "Franco Luambo Luanzo Makiadi's fans mark 35 years since death". Daily Nation. Nairobi, Kenya. Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ Montaz, Leo (8 March 2024). ""Lêkê", music in sandals". Pan African Music. Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ "Franco Luambo". Rolling Stone Australia. 15 October 2023. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ Ossinondé, Clément (5 October 2009). "Le souvenir de Luambo Makiadi Franco et l'Ok Jazz" [The memory of Luambo Makiadi Franco and Ok Jazz]. Congopage (in French). Retrieved 22 August 2024.

- ^ Haugerud, Angelique; Stone, Margaret Priscilla; Little, Peter D., eds. (2000). Commodities and Globalization: Anthropological Perspectives. Lanham, Maryland, United States: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 36–37. ISBN 978-0-8476-9943-8.

- ^ Martin, Phyllis (8 August 2002). Leisure and Society in Colonial Brazzaville. Cambridge, England, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-521-52446-9.

- ^ Ellingham, Mark; Trillo, Richard; Broughton, Simon, eds. (1999). World Music: Africa, Europe and the Middle East. London, England, United Kingdom: Rough Guides. p. 460. ISBN 978-1-85828-635-8.

- ^ a b "The mixed legacy of DRC musician Franco". New African. London, England, United Kingdom. 15 August 2018. Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ The World of Music, Volume 36. Kassel, Hesse, Germany: Bärenreiter Kassel. 1994. p. 69.

- ^ Mpisi, Jean (2003). Tabu Ley "Rochereau": innovateur de la musique africaine (in French). Paris, France: Éditions L'Harmattan. p. 185. ISBN 978-2-7475-5735-1.

- ^ Ngaira, Amos (28 November 2020). "A tale of polemic music and politics in the Congo". Daily Nation. Nairobi, Kenya. Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ Nkenkela, Auguste Ken (28 December 2023). "Les souvenirs de la musique congolaise: l'activisme de Luambo Makiadi Franco dans la politique et le sport au Zaïre" [Memories of Congolese Music: Luambo Makiadi Franco's Activism in Politics and Sports in Zaire]. Adiac-congo.com (in French). Brazzaville, Republic of the Congo. Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ "Franco: A Musician in Service of Mobutu?". Innovativeresearchmethods.org. 25 February 2019. Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ White, Bob W. (27 June 2008). Rumba Rules: The Politics of Dance Music in Mobutu's Zaire. Durham, North Carolina, United States: Duke University Press. pp. 79–81. ISBN 978-0-8223-4112-3.

- ^ a b Stewart, Gary (2003). Rumba on the River: A History of the Popular Music of the Two Congos. Verso. pp. 292–293. ISBN 978-1-85984-368-0.

- ^ "Forum: Who is your African Icon?". BBC. Broadcasting House, London, England. 6 September 2011. Retrieved 25 October 2024.

- ^ Kisangani, Emizet Francois; Bobb, Scott F. (1 October 2009). Historical Dictionary of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Lanham, Maryland, United States: Scarecrow Press. pp. 316–317. ISBN 978-0-8108-6325-5.

- ^ Hardy, Phil; Laing, Dave (21 August 1995). The Da Capo Companion To 20th-century Popular Music. Boston, Massachusetts, United States: Da Capo Press. p. 335. ISBN 978-0-306-80640-7.

- ^ Wheeler, Jesse Samba Samuel (1999). Made in Congo: Rumba Lingala and the Revolution in Nationhood. Madison, Wisconsin, United States: University of Wisconsin--Madison. p. 72.

- ^ Nkenkela, Auguste Ken (19 January 2024). "Les souvenirs de la musique congolaise: biographie et discographie de Luambo Makiadi Franco" [Memories of Congolese music: biography and discography of Luambo Makiadi Franco]. Adiac-congo.com (in French). Brazzaville, Republic of the Congo. Retrieved 9 October 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Diop, Jeannot Ne Nzau (21 October 2006). "Congo-Kinshasa: In Memoriam - Franco Luambo Makiadi (1938-1989), sa vie et son oeuvre" [Congo-Kinshasa: In Memoriam - Franco Luambo Makiadi (1938-1989), his life and work]. Le Potentiel (in French). Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Retrieved 9 October 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ossinonde, Clément (12 October 2020). "Dossier - Luambo-Makiadi "Franco", comme vous ne l'avez jamais connu" [File - Luambo-Makiadi "Franco", as you never knew him]. Congopage (in French). Retrieved 22 August 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az Ossinondé, Clément (5 October 2009). "Le souvenir de Luambo Makiadi Franco et l'Ok Jazz" [The memory of Luambo Makiadi Franco and Ok Jazz]. Congopage (in French). Retrieved 22 August 2024.

- ^ Stewart, Gary (17 November 2003). Rumba on the River: A History of the Popular Music of the Two Congos. Verso. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-85984-368-0.

- ^ Page, Thomas (8 December 2015). "The Kinshasa cowboys: How Buffalo Bill started a subculture in Congo". CNN. Retrieved 8 August 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Stewart, Gary (2000). Rumba on the river : a history of the popular music of the two Congos. London: Verso. ISBN 1-85984-744-7.

- ^ Ossinondé, Clément (2 September 2019). "Les 5 pylônes des éditions musicales congolaises "Loningisa" (1950-1962)" [The 5 pylons of the Congolese musical editions "Loningisa" (1950-1962)]. Congopage (in French). Retrieved 9 October 2024.

- ^ Tchebwa, Manda (9 August 1996). Terre de la chanson: La musique zaïroise hier et aujourd'hui (in French). De Boeck Supérieur. p. 77. ISBN 978-2-8011-1128-4.

- ^ Mpisi, Jean (2003). Tabu Ley "Rochereau": innovateur de la musique africaine (in French). Paris, France: Éditions L'Harmattan. p. 72. ISBN 978-2-7475-5735-1.

- ^ a b Stewart, Gary (17 November 2003). Rumba on the River: A History of the Popular Music of the Two Congos. Verso. p. 54. ISBN 978-1-85984-368-0.

- ^ a b Tchebwa, Manda (9 August 1996). Terre de la chanson: La musique zaïroise hier et aujourd'hui (in French). De Boeck Supérieur. p. 113. ISBN 978-2-8011-1128-4.

- ^ Yongolo, Mathieu (26 September 2024). Un jour, une chanson [One day, one song] (in French). Paris, France: Éditions L'Harmattan. p. 23. ISBN 978-2-336-46556-2.

- ^ a b c d Nickson, Chris (2006). "Franco: artist biography". All Music. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- ^ Yongolo, Mathieu (26 September 2024). Un jour, une chanson (in French). Paris, France: Éditions L'Harmattan. p. 27. ISBN 978-2-336-46556-2.

- ^ Kalumvueziko, Ngimbi (6 July 2020). Congolia. Des histoires congolaises, des souvenirs et des chants qui parlent (in French). Paris, France: Éditions L'Harmattan. p. 26. ISBN 978-2-14-015350-1.

- ^ a b "The mixed legacy of DRC musician Franco". New African. London, England, United Kingdom. 15 August 2018. Retrieved 7 October 2024.

- ^ a b c "The Return of the Rumba. "Franco, The Sorcerer of the Guitar"". Afro-Sonic Mapping. 16 January 2019. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Graham, Ronnie (1988). The Da Capo guide to contemporary African music. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80325-9.

- ^ a b c Stewart, Gary. "Franco (Luambo Makiadi, François)". Rumba on the River: Web home of the book. Retrieved 20 November 2020.

- ^ a b c Mukanga, Emmanuel N. (14 May 2021). The Discarded Brick Volume 1: An African Autobiography in 26 countries on 3 continents. A trilogy in 3 seasons. Chennai, India: Notion Press. ISBN 978-1-63873-580-9.

- ^ a b c Mayizo, Kerwin (24 May 2022). ""Kinsiona": when Franco cried over his great little brother". Pan African Music. Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ Nyota Afrika (in Swahili). Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: National Housing Corporation. 1974. p. 15.

- ^ "The day Franco brought down Kisumu walls!". Lughayangu. 12 July 2021. Retrieved 10 January 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Franco Luambo and Mobutu Sese Seko a strange relationship". Kenya Page. Nairobi, Kenya. 8 November 2015. Retrieved 6 October 2024.

- ^ Browning, Boo (12 November 1983). "Franco & the International Language Of Music". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C., United States. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 9 October 2024.

- ^ a b c Pareles, Jon (29 October 1989). "POP View: The Influential and Joyous Legacy of Zaire's Franco". The New York Times. New York, New York, United States. Retrieved 7 October 2024.

- ^ a b Pareles, Jon (28 April 1985). "CRITICS' CHOICES; Jazz/Pop". The New York Times. New York, New York, United States. Retrieved 7 October 2024.

- ^ Talking Drums, Volume 2, Issues 1-25. Talking Drums. 1984. p. 20.

- ^ "Franco Luambo Makiadi (1938 - 1989) of Zaire (Democratic Republic of the Congo) with TPOK Jazz at Hammersmith Palais". Performingartsimages.photoshelter.com. 23 April 1984. Retrieved 11 October 2024.

- ^ Piantadosi, Roger (19 October 1984). "Nightlife, the Right Life". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C., United States. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 9 October 2024.

- ^ "The George Washington University student paper notes". Archive.org. Washington, D.C., United States. 1 November 1984.

- ^ Stewart, Gary (2003). Rumba on the River: A History of the Popular Music of the Two Congos. Verso. pp. 292–293. ISBN 978-1-85984-368-0.

- ^ ""Mario": Franco's biggest hit now has a video with lyrics". Pan African Music. 4 May 2022. Retrieved 7 October 2024.

- ^ "Mario: le plus grand succès de Franco, en vidéo sous-titrée" [Mario: Franco's greatest success, in subtitled video]. Pan African Music (in French). 10 October 2019. Retrieved 17 August 2024.

- ^ "African Pop Music". The New York Times. New York, New York, United States. 26 April 1985. Retrieved 9 October 2024.

- ^ Barlow, Sean; Eyre, Banning (6 October 2021). "Franco Speaks (1985)". Afropop Worldwide. New York, New York, United States. Retrieved 7 October 2024.

- ^ "TPOK Jazz In The Mid 1980s". Kenyapage.net. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ^ MB, Harry (16 June 2021). Arianda, Jimmy (ed.). "The Female Vocal Experiment in T.P O.K Jazz: Hit or Miss?". Hakika News. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ^ "Biographie de Jolie Detta Kamenga Kayobote/Sœur Myriam". Kin kiesse (in French). Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo. 1 October 2021. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ^ Afrique magazine, Issues 220-232 (in French). Paris, France: Jeune Afrique. 2004. p. 67.

- ^ MB, Harry (16 June 2021). Arianda, Jimmy (ed.). "The Female Vocal Experiment in T.P O.K Jazz: Hit or Miss?". Hakika News. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ^ Afrique magazine, Issues 220-232 (in French). Paris, France: Jeune Afrique. 2004. p. 67.

- ^ Musica (10 June 2014). "Layile by Franco feat Jolie Detta (translated)". Kenya Page. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ^ a b "An Introduction to Franco Luambo Makiadi". kenyapage.net. Nairobi, Kenya. Retrieved 12 October 2024.

- ^ a b Smith, C.C. (12 October 2020). "Franco's Final Concert". Afropop Worldwide. New York, New York, United States. Retrieved 7 October 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Stewart, Gary (17 November 2003). Rumba on the River: A History of the Popular Music of the Two Congos. Verso. pp. 360–361. ISBN 978-1-85984-368-0.

- ^ Picard, Maurin (8 June 2022). "Congo: quand la CIA était chargée d'éliminer Patrice Lumumba" [Congo: When the CIA was tasked with eliminating Patrice Lumumba]. Le Figaro (in French). Paris, France. Retrieved 6 October 2024.

- ^ "La mort de Lumumba, une mission du MI6?" [Lumumba's death, an MI6 mission?]. Le Monde (in French). Paris, France. 2 April 2013. Retrieved 6 October 2024.

- ^ Picard, Maurin (13 June 2022). "RD Congo: "Les Etats-Unis ont tiré les ficelles derrière l'assassinat de Patrice Lumumba"" [DR Congo: "The United States pulled the strings behind the assassination of Patrice Lumumba"]. Le Soir (in French). Brussels, Belgium. Retrieved 6 October 2024.

- ^ a b c Sy, Kalidou (1 April 2014). "Les USA assassinent Lumumba... et assument !" [The USA assassinates Lumumba... and takes responsibility!]. Survie (in French). Retrieved 6 October 2024.

- ^ Toussaint, Eric (17 January 2021). "In memory of Patrice Lumumba, assassinated on 17 January 1961". Committee for the Abolition of Illegitimate Debt. Retrieved 6 October 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Franco Luambo and Mobutu Sese Seko a strange relationship". Kenya Page. Nairobi, Kenya. 8 November 2015. Retrieved 6 October 2024.

- ^ Williams, Susan (10 August 2021). White Malice: The CIA and the Covert Recolonization of Africa. New York, New York, United States: PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-1-5417-6828-4.

- ^ Stewart, Gary (June 1992). Breakout: Profiles in African Rhythm. Chicago, Illinois, U.S.: University of Chicago Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-226-77406-0.

- ^ Says, Felix Muthamia Mworia (2 June 2008). "ExecutedToday.com » 1966: Evariste Kimba and three other "plotters" against Mobutu". Executedtoday.com. Retrieved 6 October 2024.

- ^ Say, Michel-Ange Mupapa (2004). Le Congo et l'Afrique à l'orée du troisième millénaire: la pathogénie d'un sous-développement (in French). Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo: Presses universitaires du Congo. p. 214.

- ^ "100,000 in Congo See Hanging Of Ex-Premier and 3 Others". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- ^ Aguilar, Mario I. (17 April 2015). Religion, Torture and the Liberation of God. Oxfordshire, United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis. p. 26. ISBN 978-1-317-50309-5.

- ^ a b c d e Mukuna, Kazadi Wa (7 December 2014). "A brief history of popular music in DRC". Music In Africa. Retrieved 6 October 2024.

- ^ Kamba, Jonathan; Djao, Alain (April 2024). "Revisiter l'ideologie de "l'authenticite" de mobutu" [Revisiting Mobutu's ideology of "authenticity"] (PDF). Revues.acaref.net (in French). pp. 132–149. Retrieved 6 October 2024.

- ^ Kakama, Mussia (1983). "« Authenticité », un système lexical dans le discours politique au Zaïre". Mots. Les Langages du Politique. 6 (1): 31–58. doi:10.3406/mots.1983.1095.

- ^ Erenberg, Lewis A. (14 September 2021). The Rumble in the Jungle: Muhammad Ali and George Foreman on the Global Stage. Chicago, Illinois, United States: University of Chicago Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-226-79234-7.

- ^ "Mariama". Concertzender. 26 September 2020. Retrieved 7 October 2024.

- ^ "Papa Wemba". Redbullmusicacademy.com. Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- ^ Braun, Ken. "Zaire 74 – The African Artists". Rootsworld.com. Retrieved 27 September 2024.

- ^ Clewley, John (27 August 2024). "Say it loud". Bangkok Post. Bangkok, Thailand. Retrieved 27 September 2024.

- ^ Morgan, Andy (2020). "Sebene Heaven: The bittersweet paradox of Congolese music" (PDF). London, England, United Kingdom: World Music Method Ltd. pp. 22–23. Retrieved 17 August 2024.

- ^ ""Our candidate is Mobutu": Propaganda in "Candidat na biso Mobutu" (1984) – Innovative Research Methods". Innovativeresearchmethods.org. 25 February 2019. Retrieved 17 August 2024.

- ^ Morgan, Andy (2020). "Sebene Heaven: The bittersweet paradox of Congolese music" (PDF). London, England, United Kingdom: World Music Method Ltd. pp. 22–23. Retrieved 17 August 2024.

- ^ ""Our candidate is Mobutu": Propaganda in "Candidat na biso Mobutu" (1984) – Innovative Research Methods". Innovativeresearchmethods.org. 25 February 2019. Retrieved 17 August 2024.

- ^ Morgan, Andy (2020). "Sebene Heaven: The bittersweet paradox of Congolese music" (PDF). London, England, United Kingdom: World Music Method Ltd. pp. 22–23. Retrieved 17 August 2024.

- ^ ""Our candidate is Mobutu": Propaganda in "Candidat na biso Mobutu" (1984) – Innovative Research Methods". Innovativeresearchmethods.org. 25 February 2019. Retrieved 17 August 2024.

- ^ Mulera, Muniini K. (27 October 2020). "Franco, Mobutu and the folly of power". Daily Monitor. Kampala, Uganda. Retrieved 17 August 2024.

- ^ Seaman, Jacobs Odongo (13 October 2022). "Franco: Another 33 years later and rumba legend remains an enigma". Daily Monitor. Kampala, Uganda. Retrieved 17 August 2024.

- ^ Morgan, Andy (2020). "Sebene Heaven: The bittersweet paradox of Congolese music" (PDF). London, England, United Kingdom: World Music Method Ltd. pp. 22–23. Retrieved 17 August 2024.

- ^ Grice, Carter (1 November 2011). "Happy are those who sing and dance: Mobutu, Franco, and the struggle for Zairian identity" (PDF). Greensboro, North Carolina, United States: UNCG University Libraries. Retrieved 17 August 2024.

- ^ a b c "Franco Luambo death, Forever, Non Stop, Attensione Na SIDA, Sadou, La Vie des hommes". kenyapage.net. Nairobi, Kenya. Retrieved 7 October 2024.

- ^ Uwechue, Raph (1991). Makers of Modern Africa (Second ed.). United Kingdom: Africa Books Limited. pp. 237–238. ISBN 0903274183.

- ^ Niarchos, Nicolas (25 June 2019). "The Death of Simaro Lutumba Closes a Chapter of Congolese Music". The New Yorker. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- ^ "The mixed legacy of DRC musician Franco". New African Magazine. 15 August 2018. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- ^ Schnabel, Tom (4 August 2020). "Spotlight on Congolese Superstar Franco". KCRW. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- ^ Appiah, Anthony; Gates (Jr.), Henry Louis, eds. (2010). Encyclopedia of Africa, Volume 1. Oxford, England, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. p. 261. ISBN 978-0-19-533770-9.

- ^ The New Yorker, Volume 78, Issues 27-35. F-R Publishing Corporation. 2002. p. 116.

- ^ Ewens, Graeme (4 January 1994). "Discography". Congo Colossus: The Life and Legacy of Franco & OK Jazz. Buku Press. 270-306 320 pages. ISBN 978-0952365518.

- ^ "Franco & le TPOK Jazz – 'Francophonic'". Brave New World (blog). 20 May 2012. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ Johnston, Alistair. "Congo part 3". muzikifan. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ "O.K. Jazz - The Loningisa Years 1956-1961 2xLP". Aguirre Records. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ "New release: Franco & l'orchestre O.K. Jazz – La Rumba de mi Vida". Planet Ilunga. 21 January 2020. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ a b Giola, Ted. "The James Brown of Africa (Part Two)". Jazz.com. Archived from the original on 28 September 2012. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- ^ Lusk, Jon (22 September 2007). "Madilu System (obituary)". The Independent. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ^ Johnston, Alastair. "Congo part 1". Muzikifan.

- ^ Denselow, Robin (14 November 2008). "CD: Franco & Le TPOK Jazz, Francophonic Vol. 1". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

Further reading

[edit]- Ewens, Graeme (1994). Congo Colossus: The Life and Legacy of Franco & OK Jazz. North Walsham, Norfolk: Buku Press. ISBN 978-0952365518.

- Stewart, Gary (2004). Rumba on the River: A History of the Popular Music of the Two Congos. Verso. ISBN 978-1859843680.

External links

[edit]- Discography of Franco & OK Jazz

- A fan page for Franco and OK Jazz describing events decade by decade

- 1983 Interview with Franco

- Liner notes from Franco phonic – Vol. 1: 1953–1980 Archived 19 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine by Ken Braun / Sterns Music Archived 17 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine