Henry Hobson Richardson

H. H. Richardson | |

|---|---|

Detail from portrait by Hubert von Herkomer | |

| Born | September 29, 1838 Vacherie, Louisiana, U.S. |

| Died | April 27, 1886 (aged 47) Brookline, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Alma mater | Harvard College, Tulane University, École des Beaux Arts |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Buildings | Trinity Church, Boston |

| Design | Richardsonian Romanesque |

Henry Hobson Richardson, FAIA (September 29, 1838 – April 27, 1886) was an American architect, best known for his work in a style that became known as Richardsonian Romanesque. Along with Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright, Richardson is one of "the recognized trinity of American architecture."[1]

Biography

[edit]Early life

[edit]Richardson was born at the Priestley Plantation in St. James Parish, Louisiana,[2][3] and spent part of his childhood in New Orleans, where his family lived on Julia Row in a red brick house designed by the architect Alexander T. Wood.[4] He was the great-grandson of inventor and philosopher Joseph Priestley, who is usually credited with the discovery of oxygen.[5]

Richardson went on to study at Harvard College and Tulane University. Initially, he was interested in civil engineering, but shifted to architecture, which led him to go to Paris in 1860 to attend the famed École des Beaux Arts in the atelier of Louis-Jules André. He was only the second U.S. citizen to attend the École's architectural division—Richard Morris Hunt was the first[6]—and the school was to play an increasingly important role in training Americans in the following decades.

He did not finish his training there, as family backing failed due to the U.S. Civil War.[7]

Career

[edit]

Richardson returned to the U.S. in 1865, settling in New York that October. He found work with a builder, Charles,[who?] whom he had met in Paris. The two worked well together but Richardson was not being challenged. He had little to do and yearned for more. With no work Richardson fell into a state of poverty looking for more work. One of his first commissions was the William Dorsheimer House he built in 1868 for William Dorsheimer (1832–1888) on Delaware Ave in Buffalo, NY, which is in the style of the Second Empire with a Mansard roof. This important commission led to many other commissions. The style that Richardson developed over time, however, was not the more classical style of the École, but a more medieval-inspired style, influenced by William Morris, John Ruskin and Viollet le Duc.[8] Richardson developed a unique and highly personal idiom, adapting in particular the Romanesque of southern France. His early works, however, were not very remarkable. "There are few hints in the mediocre work of Richardson's early years of what was to come in his maturity, when, beginning with his competition-winning design ... for the Brattle Square Church in Boston, he adopted the Romanesque."[9]

In 1869, he designed the Buffalo State Asylum for the Insane (now known as the Richardson Olmsted Complex) in Buffalo, the largest commission of his career and the first appearance of Richardsonian Romanesque style. A massive Medina sandstone complex, it is a National Historic Landmark and, as of 2009, was being restored.[10]

Trinity Church in Boston, designed by Richardson and built 1872–1877, solidified his national reputation and led to major commissions for the rest of his life. Although incorporating historical elements from a variety of sources, including early Syrian Christian, Byzantine, and both French and Spanish Romanesque, it was more "Richardsonian" than Romanesque.[11][12] Trinity was also a collaboration with the construction and engineering firm of the Norcross Brothers, with whom the architect would work on some 30 projects.

He designed the Ames Monument, which was constructed from 1880 to 1882, and is located at the highest point of the original Transcontinental Railway (the financing of which was spearheaded by Oliver Ames Jr. and his brother Oakes Ames), east of Laramie, Wyoming. The Ames brothers and family provided generous patronage for Richardson's works, and after Oliver's death, Richardson was commissioned to design the Ames Free Library established in 1883 by a bequeath in Ames's will.

He was well-recognized by his peers; of ten buildings named by American architects as the best in 1885, fully half were his: besides Trinity Church, there were Albany City Hall, Sever Hall at Harvard University, the New York State Capitol in Albany (as a collaboration), and Oakes Ames Memorial Hall in North Easton, Massachusetts.

Despite the success of Trinity, Richardson built only two more churches, focusing instead on the monumental buildings he preferred, plus libraries, railroad stations, commercial buildings, and houses.[13] Of his buildings, the two he liked best, the Allegheny County Courthouse (Pittsburgh, 1884–1888) and the Marshall Field Wholesale Store (Chicago, 1885–1887, demolished 1930), were completed posthumously by his assistants.[14]

Later years

[edit]Richardson spent much of his later years in his house at 25 Cottage St. in Brookline, Massachusetts,[15] which had a studio attached.

Richardson died in 1886 at age 47 of Bright's disease.[16] On his last day, he signed an informal will directing the three assistants still remaining to carry on the business, which was soon formalized as Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge.[17] One example includes Richardson's design for the Greater Cincinnati Chamber of Commerce Building. Richardson had won the selection process in 1885 and nearly finalized the work, but after his death his successors completed the project.[18]

He was buried in Walnut Hills Cemetery, Brookline, Massachusetts. Despite an enormous income for an architect of his day, his "reckless disregard for financial order" meant that he died deeply in debt, leaving little to his widow and six children.[19]

Major work

[edit]Trinity Church

[edit]Richardson's most acclaimed early work is Trinity Church.[9] The interior of the church is one of the leading examples of the arts and crafts aesthetic in the United States. It was at Trinity that Richardson first worked with Augustus Saint Gaudens, with whom he would work many times in the ensuing years. Across the square is the Boston Public Library, built later (1895) by Richardson's former draftsman, Charles Follen McKim. Together these and the surrounding buildings comprise one of the outstanding American urban complexes, built as the centerpiece of the newly developed Back Bay.

Richardson Olmsted Campus

[edit]The largest building complex of HH Richardson's career, Richardson Olmsted Complex in Buffalo, New York, United States was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1986. The first building to display his characteristic style the complex of buildings was designed in concert with the famed landscape team of Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux in the late 1800s, incorporating a system of enlightened treatment for people with mental illness developed by Dr. Thomas Story Kirkbride. Over the years, as mental health treatment changed and resources were diverted, the buildings and grounds began a slow deterioration. In 2006, the Richardson Center Corporation was formed with a mandate to save the buildings and bring the Campus back to life through a state appropriation.

Today, the Richardson Olmsted Campus is being transformed into a cultural amenity for the city. Arriving in 2018, the Richardson Olmsted Campus will also have the Lipsey Architecture Center of Buffalo. The remaining buildings have been stabilized pending future opportunities.

Building types

[edit]

Richardson pointedly claimed ability to create any type of structure a client wanted, insisting he could design anything "from a cathedral to a chicken coop."[20] "The things I want most to design are a grain elevator and the interior of a great river-steamboat."[13] However, architectural historian James F. O'Gorman sees Richardson's achievement particularly in four building types: public libraries, commuter train station buildings, commercial buildings, and single-family houses.

Public libraries

[edit]A series of small public libraries donated by patrons for the improvement of New England towns makes a small coherent corpus that defines Richardson's style: Winn Memorial Library (Woburn), Ames Free Library (Easton), the Converse Memorial Library (Malden), and the Thomas Crane Public Library (Quincy), (1880–1882) "generally regarded by architectural historians as the masterpiece of Richardson's libraries",[21] the Hubbard Memorial Library (Ludlow, Massachusetts), and Billings Memorial Library on the campus of the University of Vermont.[22] These buildings seem resolutely anti-modern, with the atmosphere of an Episcopalian vicarage, dimly lit for solemnity rather than reading on site. They are preserves of culture that did not especially embrace the contemporary flood of newcomers to New England. Yet they offer clearly defined spaces, easy and natural circulation, and they are visually memorable. Richardson's libraries found many imitators in the "Richardsonian Romanesque" movement.

The Thomas Crane Public Library is regarded as the best of Richardson's libraries.[23][24][25] In his earlier libraries, Richardson's approach was to conceive the parts and then assemble them, while in the later ones such as Crane he thought in terms of the whole.[26] Richardson also engaged in a process of simplification and elimination with each successive library, until in Crane "Richardson's concentration on the relation of solid to void, of wall to window, becomes the basis for a harmonious abstraction with scarcely a reference to any past style."[24][27]

Railroad buildings

[edit]

Richardson also designed nine railroad station buildings for the Boston & Albany Railroad as well as three stations for other lines.[28] More subtle than his churches, municipal buildings and libraries, they were an original response to this relatively new building type. Beginning with his first at Auburndale (1881, demolished 1960s), Richardson drew inspiration for these station buildings from Japanese architecture that he learned about from Edward S. Morse, a Harvard zoologist who began traveling to Japan in 1877, originally for biological specimens. Falling in love with Japan, upon his return that same year Morse began giving illustrated "magic lantern" public lectures on Japanese ceramics, temples, vernacular architecture, and culture.[29] Richardson incorporated Japanese concepts "in both sihouette and spatial concept", including the karahafu ("excellent gable", but generally poorly translated as "Chinese gable" despite its Japanese origin), the eyelid dormer, and the wide hip roof with extended eaves, all shown by Morse.[30]

Among the few stations still extant, these influences are perhaps best illustrated in his Old Colony station (Easton, Massachusetts, 1881–1884).[31] Here he uses the Syrian arch that became a hallmark of Richardson designs for both the porte-cochère and the windows of the main structure. Reminiscent of a courtyard and temple that Morse illustrated from Nikkō in Tochigi prefecture, Japan, the hip roof on wide, bracketed eaves nearly hides the rough stonework below in shadow. Richardson even included a carved dragon at each end of the beam spanning the arches of windows.[32] The walls "become horizontal planes hovering above one another with bands of windows in between."[33]

Richardson was an early although not the first U.S. architect to look to Japan, but his train stations "form the earliest sustained application of Japanese inspiration in American architecture, an undeniable precursor to Frank Lloyd Wright's Prairie house designs".[33] As with his libraries, Richardson evolved and simplified as the series continued, and his famous Chestnut Hill station (Newton, Massachusetts, 1883–1884, demolished circa 1960) featured clean lines with less Japanese influence.[33]

After his death, more than 20 other stations were designed in Richardson's style for the Boston and Albany line by the firm of Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge, all draftsmen of Richardson at the time of his death.[28] Many Boston and Albany stations were landscaped by Richardson's frequent collaborator, Frederick Law Olmsted. Additionally, a railroad station in Orchard Park, New York (near Buffalo) was built in 1911 as a replica of Richardson's Auburndale station in Auburndale, Massachusetts. The original Auburndale station was torn down in the 1960s during construction of the Massachusetts Turnpike. The original Richardson stations on the Boston and Albany Highland branch have either been demolished or converted to new uses (such as restaurants). Two of the stations designed by Shepley, Rutan, and Coolidge (both in Newton, Massachusetts) are still used by Boston's MBTA (green line) public transit service: and Newton Highlands station and Newton Centre station.

Commercial buildings

[edit]

The noted Marshall Field Wholesale Store (Chicago, 1885–1887, demolished 1930) is Richardson's "culminating statement of urban commercial form", and its remarkable design influenced Louis Sullivan, Frank Lloyd Wright, and many other architects.[34] According to Jeffrey Karl Ochsner, who has compiled all of Richardson's architectural works, despite its demolition in 1930, the Marshall Field Wholesale Store "is probably the most famous of Richardson's buildings, one that Richardson himself saw as among his most significant."[35] Architectural critic Henry-Russell Hitchcock states that in the Field Store, Richardson "was, perhaps, never more creative architecturally."[36] Drawing from his own earlier work and both Romanesque and Renaissance precedents, Richardson designed this "massive but integrated" seven-story stone warehouse.[37] Minimizing ornamentation in an era that employed much of it, he stressed what he termed "the beauty of material and symmetry rather than mere superficial ornamentation" with "the effects depending on the relations of 'voids and solids'... on the proportion of the parts."[38] Not requiring the new steel frame technology because of its comparatively low height, Richardson used multi-storied windows topped by arches to tie the stories together, and the regular patterns of the windows to tie the entire building into "a simple and unified solid occupying an entire block."[39]

Single-family houses

[edit]Richardson designed many important single-family residences, but his famous John J. Glessner House (Chicago, 1885–87) is his best and most influential urban house. The Mary Fisk Stoughton House (Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1882–1883), the Henry Potter House (St. Louis, 1886–1887, demolished 1958), and the Robert Treat Paine Estate (aka Stonehurst) (Waltham, Massachusetts, 1886) play that role for suburban and country settings.[40] The Glessner House in particular influenced Frank Lloyd Wright as he began developing what would become his Prairie School houses.[41] With his house for Reverend Percy Browne (Marion, Massachusetts, 1881–82) Richardson revived "the old colonial form (of the gambrel roof) to shape the facade of an artistically ambitious house. Perhaps he used the gambrel to signify the humility appropriate to the profession of his client, but in doing so he sanctioned its use for wealthier patrons and by other architects. Within three years the crumpled gambrel profile was showing up everywhere" and became one of the notable features of Shingle Style architecture.[42]

Richardsonian Romanesque

[edit]Richardson is one of few architects to be immortalized by having a style named after him. "Richardsonian Romanesque", unlike Victorian revival styles like Neo-Gothic, was a highly personal synthesis of the Beaux-Arts predilection for clear and legible plans, with the heavy massing that was favored by the pro-medievalists. It featured picturesque roofline profiles, rustication and polychromy, semi-circular arches supported on clusters of squat columns, and round arches over clusters of windows on massive walls.

Following his death, the Richardsonian style was perpetuated by a variety of proteges and other architects, many for civic buildings like city halls, county buildings, court houses, train stations and libraries, as well as churches and residences. These include:

- the successor firm of Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge, who completed some two dozen unfinished projects and then continued to produce work in the same style, and continued to employ his collaborators the Norcross Brothers for construction and engineering expertise, Frederick Law Olmsted for landscape architecture, and the English sculptor John Evans for stonecarving

- Stanford White and Charles Follen McKim, who worked in Richardson's office as young men, went on to form McKim, Mead and White and moved into the radically different Beaux-Arts architecture style

- Richardson's great admirer Louis Sullivan adapted Richardson's characteristic lessons of texture, massing, and the expressive language of stone walling (see Richardson's noted Chicago building Marshall Field's Wholesale Store), particularly at Chicago's Auditorium Building, and these influences are detectable in the work of Sullivan's own student Frank Lloyd Wright.

- Richardson found sympathetic reception among young Scandinavian architects of the following generation, notably Eliel Saarinen.

- The Patrick F. Taylor Library, formerly known as the Howard Memorial Library, was built soon after Richardson's death. It is sometimes called "the only Richardson building located in the South".[43] Residents of New Orleans had wanted an example of Richardson's work, a native son of New Orleans. The office of Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge used a Richardson design which had been submitted and rejected some years earlier for a library in Saginaw, Michigan. This leads some, particularly those in New Orleans, to argue that the building can be said to be by Richardson; the counter argument is that the design was not originally intended for this location and the building was constructed after Richardson's death with no input from the architect beyond the initial design. The library building is currently part of the Ogden Museum of Southern Art.

- The Amelia S. Givin Library in Mount Holly Springs, PA was designed by James T. Steen, a well known Pittsburgh architect who worked extensively in the Richardsonian Romanesque style. The Givin Library was built in 1889 in the Richardsonian style. Its interior was finished in an Orientalism theme which used the 1885 patented Moorish Fretwork screens of Moses Younglove Ransom. The Givin Library is still in use as a public library.

Replicas

[edit]Although many structures exist in the Romanesque style and some borrow so heavily that they are often mistaken for Richardson designs, several buildings have been built specifically to mimic a single Richardson structure.

- Wellesley Farms Railroad Station – This structure was built by Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge (draftsmen of Richardson) soon after Richardson's death. Although this firm built many stations in Richardson's style, they were specifically penalized[by whom?] for this one because it was so similar to Richardson's Eliot station in Newton, Massachusetts.[44] Eliot station was torn down in the 1950s.[citation needed]

- A railroad station in Orchard Park, New York (near Buffalo), was built in 1911 as a replica of Richardson's Auburndale station in Auburndale, Massachusetts. The original Auburndale station, Richardson's first for the Boston & Albany Railroad and which was described by Henry Russell Hitchcock as "the best he ever built",[45] was torn down in the 1960s during construction of the Massachusetts Turnpike.[citation needed]

- The Old Orange County Courthouse in Santa Ana, California, was completed in 1906 and is heavily influenced by Richardson's designs, bearing a strong resemblance to Richardson's Sever Hall at Harvard.[citation needed]

- Castle Hill Light is a lighthouse in Newport, Rhode Island, which is often attributed to Richardson. Richardson drew a sketch for the lighthouse at that location which may have been the basis for the design, though the actual structure does not include the residence featured in Richardson's sketch.[citation needed]

Chronological list of works

[edit]

This is a partial list of works by Richardson:[46]

- 1867 Church of the Unity – Springfield, Massachusetts

- 1867 Western Railroad Offices – Springfield, Massachusetts

- 1867 Grace Episcopal Church – Medford, Massachusetts

- 1868 Benjamin W. Crowninshield House – Boston, Massachusetts

- 1868 H. H. Richardson House – Clifton, Staten Island, New York

- 1868 Alexander Dallas Bache Monument – Washington, DC

- 1868 William Dorsheimer House – Buffalo, New York

- 1869 Agawam National Bank – Springfield, Massachusetts

- 1869 Brattle Square Church (now First Baptist Church) – Boston, Massachusetts

- 1869 New York State Asylum – Buffalo, New York

- 1869 Worcester High School – Worcester, Massachusetts

- 1871 Hampden County Courthouse – Springfield, Massachusetts

- 1871 North Congregational Church – Springfield, Massachusetts

- 1872 Trinity Church – Boston, Massachusetts (National Historic Landmark)

- 1872 Frank William Andrews House – Newport, Rhode Island

- 1874 William Watts Sherman House – Newport, Rhode Island

- 1875 Hayden Building – Boston, Massachusetts

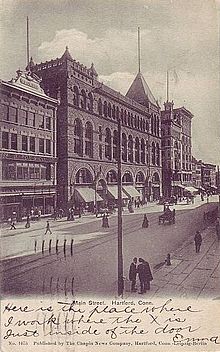

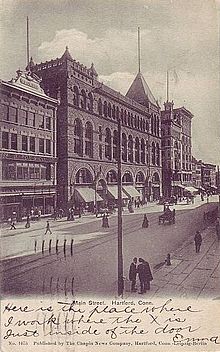

- 1875 R. and F. Cheney Building – Hartford, Connecticut

Cheney Building, Hartford, Connecticut c. 1905 - 1875 New York State Capitol – Albany, New York

- 1876 Rev. Henry Eglinton Montgomery Memorial – New York City

- 1876 Winn Memorial Library – Woburn, Massachusetts

- 1877 Oliver Ames Free Library – North Easton, Massachusetts

- 1878 Sever Hall – Cambridge, Massachusetts

- 1879 Oakes Ames Memorial Hall – North Easton, Massachusetts

- 1879 Rectory for Trinity Church – Boston, Massachusetts

- 1879 Ames Monument – Sherman, Wyoming

- 1880 F.L. Ames Gate Lodge – North Easton, Massachusetts

- 1880 Bridge in the Fenway – Boston, Massachusetts

- 1880 Stony Brook Gatehouse – Boston, Massachusetts

- 1880 Thomas Crane Public Library – Quincy, Massachusetts (National Historic Landmark)

- 1880 Dr. John Bryant House – Cohasset, Massachusetts

- 1880 Albany City Hall – Albany, New York

- 1881 Austin Hall – Cambridge, Massachusetts

- 1881 Pruyn Monument – Albany, New York

- 1881 Rev. Percy Browne House – Marion, Massachusetts

- 1881 North Easton station - Old Colony Railroad Station – North Easton, Massachusetts

- 1882 Grange Sard Jr. House – Albany, New York

- 1882 Mary Fiske Stoughton House – Cambridge, Massachusetts

- 1883 Billings Memorial Library – Burlington, Vermont

- 1883 Connecticut River Railroad Station – Holyoke, Massachusetts

- 1883 Allegheny County Courthouse and Allegheny County Jail – Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

- 1883 Robert Treat Paine Estate – Waltham, Massachusetts

- 1883 Boston & Albany Railroad Station – Framingham, Massachusetts

- 1883 Billings Memorial Library – Burlington, Vermont

- 1884 Boston & Albany Railroad Station – Newton, Massachusetts

- 1884 F.L. Ames Gardener's Cottage – North Easton, Massachusetts

- 1884 Immanuel Baptist Church – Newton, Massachusetts

- 1884 Ephraim W. Gurney House – Beverly, Massachusetts

- 1884 Union Station – Palmer, Massachusetts

- 1885 Converse Memorial Library/Building – Malden, Massachusetts (National Historic Landmark)

- 1885 Benjamin H. Warder House – Washington, DC

- 1885 Bagley Memorial Fountain – Detroit, Michigan

- 1885 John J. Glessner House – Chicago, Illinois (National Historic Landmark)

- 1885 Boston & Albany Railroad Station – Wellesley Hills, Massachusetts

- 1885 Union Passenger Station – New London, Connecticut

- 1885 Emmanuel Episcopal Church – Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

- 1886 Lululaund or the Sir Hubert von Herkomer House – Bushey, Hertfordshire, England

- 1886 Dr. H.J. Bigelow House – Newton, Massachusetts

- 1886 Isaac H. Lionberger House – St. Louis, Missouri

Gallery

[edit]-

Church of the Unity (1867–68)

-

William Dorsheimer House (1868)

-

New York State Asylum (1869)

-

William Watts Sherman House (1874–76)

-

Sever Hall (1878)

-

Oakes Ames Memorial Hall (1879)

-

Great Western Staircase, New York State Capitol Building (late 1870s–80s)

-

Albany City Hall (1880)

-

North Easton station (1881)

-

Allegheny County Courthouse (1883)

References

[edit]- ^ O'Gorman, James F. (1991). Three American Architects: Richardson, Sullivan, and Wright, 1865-1915. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. xv. ISBN 978-0-226-62071-8.

- ^ Rail, Tony: "William Priestley Vindicated, with a Previously Unpublished Letter", Enlightenment and Dissent, no. 28 (2012), 150–195.

- ^ "The History of St. Joseph & Felicity – St. Joseph and Felicity Plantations". Retrieved May 12, 2024.

- ^ Mary Louise Christovich, et al. [ed.], New Orleans Architecture, v. 2: The American Sector (Gretna, LA), p. 174.

- ^ Van Rensselaer, Mariana Griswold (1959) [1888]. Henry Hobson Richardson and His Works. New York: Dover Publications, Inc. p. 1.

- ^ Van Rensselaer, Mariana Griswold (1959) [1888]. Henry Hobson Richardson and His Works. New York: Dover Publications, Inc. p. 15.

- ^ Whiffen, Marcus (1992). American Architecture Since 1780: A Guide to the Styles (Revised ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-262-73097-6.

- ^ "Henry Hobson Richardson". American Architecture Series.

- ^ a b Whiffen, Marcus; Koeper, Frederick (1981). American Architecture 1607-1976. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. p. 224. ISBN 978-0-262-23105-3.

- ^ "Buffalo State Hospital". National Historic Landmarks Program. Washington, DC: National Park Service. Archived from the original on May 2, 2008. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- ^ O'Gorman, James F. (1991). Three American Architects: Richardson, Sullivan, and Wright, 1865-1915. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-226-62071-8.

- ^ Whiffen, Marcus (1992). American Architecture Since 1780: A Guide to the Styles (Revised ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-262-73097-6.

- ^ a b Whiffen, Marcus; Koeper, Frederick (1981). American Architecture 1607-1976. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. p. 226. ISBN 978-0-262-23105-3.

- ^ Whiffen, Marcus; Koeper, Frederick (1981). American Architecture 1607-1976. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. p. 231. ISBN 978-0-262-23105-3.

- ^ Szaniszlo, Marie (December 27, 2020). "Preservationists attempt to save Brookline homes from demolition". The Boston Herald. Retrieved December 28, 2020.

- ^ O'Gorman, James F. (1997). Living Architecture: A Biography of H.H. Richardson. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-684-83618-8.

- ^ O'Gorman, James F. (1997). Living Architecture: A Biography of H.H. Richardson. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 188. ISBN 978-0-684-83618-8.

- ^ J. William Rudd (May 1968). "The Cincinnati Chamber of Commerce Building". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 27 (2): 115–123. doi:10.2307/988469. JSTOR 988469.

- ^ O'Gorman, James F. (1997). Living Architecture: A Biography of H.H. Richardson. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-684-83618-8.

- ^ Glessner, John Jacob; Foundation, Chicago Architecture (1992). The story of a house: H.H. Richardson's Glessner House. Chicago Architecture Foundation. ISBN 9780962056239.

- ^ Ochsner, Jeffrey Karl, H.H. Richardson: Complete Architectural Works, MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1982 p.227

- ^ "A Gem of Architecture: The History of The Billings Library". Researching Historic Structures and Sites. Burlington, Vermont: University of Vermont. December 2, 1999.

- ^ Ochsner, Jeffrey Karl (1982). H.H. Richardson: Complete Architectural Works. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. p. 227. ISBN 978-0-262-65015-1.

- ^ a b Whiffen, Marcus; Koeper, Frederick (1981). American Architecture 1607-1976. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. p. 227. ISBN 978-0-262-23105-3.

- ^ Hitchock, Henry-Russell (1966). The Architecture of H.H. Richardson and His Times (3rd ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-262-58012-0.

- ^ O'Gorman, James F. (1991). Three American Architects: Richardson, Sullivan, and Wright, 1865-1915. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-226-62071-8.

- ^ O'Gorman, James F. (1991). Three American Architects: Richardson, Sullivan, and Wright, 1865-1915. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-226-62071-8.

- ^ a b Ochsner, Jeffrey Karl, "Architecture for the Boston & Albany Railroad," Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 47 (June 1988), pages 109-131.

- ^ Floyd, Margaret Henderson (1997). Henry Hobson Richardson: A Genius for Architecture. New York: Monacelli Press. p. 191. ISBN 978-1-885254-70-2.

- ^ Floyd, Margaret Henderson (1997). Henry Hobson Richardson: A Genius for Architecture. New York: Monacelli Press. pp. 191–192. ISBN 978-1-885254-70-2.

- ^ Floyd, Margaret Henderson (1997). Henry Hobson Richardson: A Genius for Architecture. New York: Monacelli Press. p. 192. ISBN 978-1-885254-70-2.

- ^ Floyd, Margaret Henderson (1997). Henry Hobson Richardson: A Genius for Architecture. New York: Monacelli Press. pp. 193 and 200. ISBN 978-1-885254-70-2.

- ^ a b c Floyd, Margaret Henderson (1997). Henry Hobson Richardson: A Genius for Architecture. New York: Monacelli Press. p. 200. ISBN 978-1-885254-70-2.

- ^ O'Gorman, James F. (1991). Three American Architects: Richardson, Sullivan, and Wright, 1865-1915. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 46–54. ISBN 978-0-226-62071-8.

- ^ Ochsner, Jeffrey Karl (1982). H.H. Richardson: Complete Architectural Works. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. p. 381. ISBN 978-0-262-65015-1.

- ^ Hitchock, Henry-Russell (1966). The Architecture of H.H. Richardson and His Times (3rd ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. p. 275. ISBN 978-0-262-58012-0.

- ^ O'Gorman, James F. (1991). Three American Architects: Richardson, Sullivan, and Wright, 1865-1915. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-226-62071-8.

- ^ O'Gorman, James F. (1991). Three American Architects: Richardson, Sullivan, and Wright, 1865-1915. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-226-62071-8.

- ^ O'Gorman, James F. (1991). Three American Architects: Richardson, Sullivan, and Wright, 1865-1915. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 47–52. ISBN 978-0-226-62071-8.

- ^ O'Gorman, James F. (1991). Three American Architects: Richardson, Sullivan, and Wright, 1865-1915. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 57–58. ISBN 978-0-226-62071-8.

- ^ O'Gorman, James F. (1991). Three American Architects: Richardson, Sullivan, and Wright, 1865-1915. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-226-62071-8.

- ^ Mark Wright (March 2009). "H. H. Richardson's House for Reverend Browne, Rediscovered". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 68 (1): 74–99. doi:10.1525/jsah.2009.68.1.74. JSTOR 10.1525/jsah.2009.68.1.74.

- ^ "Museum Architecture and Design". About the O. New Orleans: Ogden Museum of Southern Art, University of New Orleans. Archived from the original on November 4, 2011. Retrieved November 7, 2011.

- ^ Roy, John H. Jr. (2007). A Field Guide to Southern New England Railroad Depots and Freight Houses. New England Rail Heritage Series. Pepperell, Massachusetts: Branch Line Press. pp. missing page citation. ISBN 978-0-942147-08-7.

- ^ Cummings, Abbott L.; Osmund R. Overby (1961). "Boston and Albany Railroad Station: Photographs, Written Historical and Descriptive Data". Historic American Buildings Survey. Washington, DC: National Park Service. p. 2.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Ochsner, Jeffrey Karl (1982). H.H. Richardson: Complete Architectural Works. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. pp. all. ISBN 978-0-262-65015-1.

Further reading

[edit]- Breisch, Kenneth A,. Henry Hobson Richardson and the Small Public Library in America: A Study in Typology, MIT Press, 1997

- Floyd, Margaret Henderson, Henry Hobson Richardson: A Genius for Architecture, Monacelli Press, NY 1997

- Hitchcock, Henry Russell, The Architecture of H. H. Richardson and His Times, Museum of Modern Art, NY 1936; 2nd ed., Archon Books, Hamden CT 1961; rev. paperback ed., MIT Press, Cambridge MA and London 1966

- Larson, Paul C., ed., with Susan Brown, The Spirit of H.H. Richardson on the Midland Prairies: Regional Transformations of an Architectural Style, University Art Museum, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and Iowa State University Press, Ames 1988

- Meister, Maureen, ed., H. H. Richardson: The Architect, His Peers, and Their Era, MIT Press, Cambridge MA 1999

- Ochsner, Jeffrey Karl, H.H. Richardson: Complete Architectural Works, MIT Press, Cambridge MA 1984

- Ochsner, Jeffrey Karl, and Andersen, Dennis A., Distant Corner: Seattle Architects and the Legacy of H. H. Richardson, University of Washington Press, Seattle 2003

- O'Gorman, James F., Living Architecture: A Biography of H. H. Richardson, Simon & Schuster, NY 1997

- O'Gorman, James F., H. H. Richardson: Architectural Forms for an American Society, University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1987

- O'Gorman, James F., H. H. Richardson and His Office: Selected Drawings, David R. Godine, Boston 1974

- Roth, Leland M., A Concise History of American Architecture, Harper & Row publishers, NY, NY 1979

- Shand-Tucci, Douglas, Built in Boston: City and Suburb, 1800 - 1950, University of Massachusetts Press, Amherst, MA 1988

- Van Rensselaer, Mariana Griswold, Henry Hobson Richardson and His Works, Dover Publications, Inc. NY 1959 (Reprint of 1888 edition)

- Van Trump, James D., "The Romanesque Revival in Pittsburgh," Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol. 16, No. 3 (October 1957), pp. 22–29

- Wright, Mark, "H. H. Richardson's House for Reverend Browne, Rediscovered," Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol. 68, No. 1 (March 2009), pp. 74–99 https://www.sah.org/docs/default-source/preservation-advocacy/2019-percy-browne-house-jsah-article.pdf

External links

[edit]- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Henry Hobson Richardson buildings

- Richardsonian Romanesque architecture

- Architects from Louisiana

- Architects from Massachusetts

- 1838 births

- 1886 deaths

- American alumni of the École des Beaux-Arts

- Harvard College alumni

- Deaths from nephritis

- People from Brookline, Massachusetts

- Historicist architects

- American railway architects

- 19th-century American architects

- Fellows of the American Institute of Architects

- Burials at Walnut Hills Cemetery (Brookline, Massachusetts)