Point Blank (1967 film)

| Point Blank | |

|---|---|

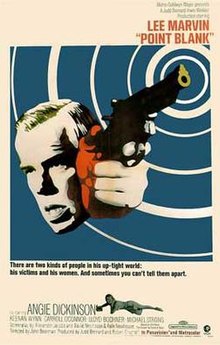

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | John Boorman |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | The Hunter 1963 novel by Richard Stark |

| Produced by | |

| Starring | Lee Marvin |

| Cinematography | Philip H. Lathrop |

| Edited by | Henry Berman |

| Music by | Johnny Mandel |

Production company | Judd Bernard-Irwin Winkler Production |

| Distributed by | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer |

Release date |

|

Running time | 92 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $2.5 million[1] |

| Box office | $9 million (rentals)[2] |

Point Blank is a 1967 American crime film directed by John Boorman, starring Lee Marvin, co-starring Angie Dickinson, Keenan Wynn and Carroll O'Connor, and adapted from the 1963 crime noir pulp novel The Hunter by Donald E. Westlake, writing as Richard Stark.[3] Boorman directed the film at Marvin's request and Marvin played a central role in the film's development. The film grossed over $9 million in theatrical rentals in 1967 and has since gone on to become a cult classic, eliciting praise from such critics as film historian David Thomson.

In 2016, Point Blank was deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" by the United States Library of Congress, and selected for preservation in its National Film Registry.[4]

Plot

[edit]Walker works with his friend Mal Reese to rob a major crime operation, ambushing the courier on deserted Alcatraz Island. After counting the money, Reese shoots Walker, leaving him for dead. Reese takes the money and Walker's wife, Lynne. Walker recovers. With assistance from the mysterious Yost, Walker sets out to find Reese and recover his half of the money; $93,000. Reese used all of the money from the job to pay back a debt to a crime syndicate called "The Organization." Walker goes to Los Angeles, where he bursts in on Lynne and riddles her bed with bullets, only to find Reese has long since disappeared. Lynne is distraught; she takes an overdose of sleeping pills.

Walker approaches car dealer Stegman for information, smashing a new car and terrorizing him until Stegman says Reese is with Walker's sister-in-law, Chris.

Breaking in on Chris, he learns that she despises Reese and admires Walker. Willing to help in any way, Chris agrees to a sexual tryst with Reese inside his heavily guarded penthouse apartment, where she will unbolt a door for Walker. Walker ties up some men in an apartment across from the penthouse and has a call made to police to report a robbery, creating a diversion that enables him to slip into the penthouse.

With a gun to Reese's head, Walker persuades him to give up the names of his Organization superiors – Carter, Brewster, and Fairfax – so he can make somebody pay back his $93,000. He then forces Reese, naked except for a bedsheet, to the balcony saying that both will go and meet Carter together. Suddenly, a bodyguard switches on the light in the room they just left, calling for Reese. Startled, Walker backs up quickly still holding on to Reese behind him by the bedsheet. Forced to back up himself, Reese accidentally goes over the side and plunges to his death. Walker, still grasping the bedsheet, watches him fall.

After next confronting Carter for his money, Walker is set up. A sniper is assigned to kill him at a money drop in the paved Los Angeles River bed. Walker, suspecting a trap, forces Carter to get the money instead. Carter and Stegman both get shot at the pickup. The sniper leaves; Walker tears open the package of money but finds only slips of blank paper.

Yost takes Walker to a house belonging to Brewster. Walker visits Chris in her apartment, which has been trashed by The Organization. He brings her with him to Brewster's house, claiming she will be safer with him. While waiting for Brewster, Chris slaps and punches Walker as he regards her impassively, not defending himself. She leaves the room. Walker hears noises from the kitchen and goes in to turn off several appliances that Chris has apparently turned on. She taunts him as "washed up" over a speaker system. He finds her playing pool; she turns on him and hits him in the head with a pool cue. They fall to the floor in an embrace, then go to bed and make love. The following morning, Brewster comes home and is ambushed by Walker, who demands his money. Walker forces Brewster to call Fairfax, but Fairfax refuses to pay. Brewster says the only cash available for Walker is in San Francisco. "The drop has changed, but the run is still the same", he explains.

At Fort Point, Walker refuses to show himself as the courier delivers the money. Hiding in the dark is the sniper, who shoots Brewster. Yost emerges from the shadows, telling Brewster that it was not Walker who shot him. Brewster calls out to Walker, "This is Fairfax, Walker! Kill him!"

Yost/Fairfax thanks Walker (who is still hiding in the darkness) for eliminating his dangerous underlings, telling him: "Our deal's done, Walker. Brewster was the last one." He offers a partnership, but Walker remains silent. Yost/Fairfax and the hitman go away while leaving the money on the ground.

Cast

[edit]- Lee Marvin as Walker

- Angie Dickinson as Chris

- Keenan Wynn as Yost

- Carroll O'Connor as Brewster

- Lloyd Bochner as Frederick Carter

- Michael Strong as Stegman

- John Vernon as Mal Reese

- Sharon Acker as Lynne

- James B. Sikking as hired gun

- Sandra Warner as waitress

Production

[edit]It was the second film produced by Irwin Winkler who had just made Double Trouble at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Winkler and Judd Bernard became enthusiastic about the Point Blank script and felt it would be ideal for Lee Marvin. They struggled to get the script to Marvin, so they sent it to John Boorman, an emerging director Winkler knew from his management days.[5]

Boorman met Marvin in London, where the actor was shooting The Dirty Dozen. Boorman and Marvin talked about a script based on the book The Hunter by Donald Westlake. Both hated the script but loved Walker the main character. When they agreed to work on the film, Marvin discarded the script and called a meeting with the head of the studio, the producers, his agent, and Boorman. As Boorman recalled, "[Marvin] said, 'I have script approval?' They said 'yes'. 'And I have approval of principal cast?'. 'Yes'. He said, 'I defer all those approvals to John [Boorman].' And he walked out. So on my very first film in Hollywood, I had final cut and I made use of it".[6]

MGM agreed to finance a budget of $2 million. MGM's head of production Robert Weitman wanted the female lead played by Stella Stevens but Boorman and Marvin insisted on Angie Dickinson. Winkler claims he was then not surprised to see Stevens cast in a subsequent MGM film, Sol Madrid.[7]

The unusual structure of the film was due in part to the original script which adhered to the non-linear structure of the novel and developments during the shooting of the film.[6][8] Rehearsals took place at Marvin's house in Los Angeles.[6] On the rehearsal day in which Marvin was to ask Sharon Acker what happened to the money, Marvin did not say his lines, forcing Acker to continue the conversation on her own. "I saw right away he was right", replied Boorman, "Lee never made suggestions. He would just show you". So Boorman changed the lines in the script so that Acker would essentially ask and answer Marvin's questions and the result is in the finished film. "It made a conventional scene something more" added Boorman.[6]

This was the first film shot at Alcatraz Island, the infamous prison in San Francisco that had closed in 1963, only three years before the production. Two weeks in the abandoned prison facility required the services of 125 crew members.[9] While Marvin and Wynn enjoyed shooting on location, Wynn was concerned about the weather and the need to loop half the dialogue.[10] During the shoot, Angie Dickinson and Sharon Acker modeled contemporary fashions for a Life Magazine exclusive against the backdrop of the prison.[9] Acker was accidentally hurt by the blanks that Vernon used to shoot at Marvin early in the film.[6]

Director Boorman chose locations that were "stark". For example, the airplane terminal walkway down which Marvin walked originally had flower pots lining the walls. Boorman had the pots taken out to "make it all bare".[6] After Boorman showed the finished cut to executives, they were "very perplexed and mumbling about reshoots". Margaret Booth, supervising film editor working for MGM, told Boorman as the execs filed out, "You touch one frame of this film over my dead body!"[6]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]The film earned $9 million in theatrical rentals during its initial release.[1]

Critical

[edit]In her 1967 New Yorker review of Bonnie and Clyde, Pauline Kael wrote: "A brutal new melodrama is called Point Blank, and it is."[11] Kael later called the film "intermittently dazzling",[12] and voted for John Boorman as Best Director in the 1967 National Society of Film Critics Awards polling.[13] Roger Ebert gave the film three out of four stars and said, "as suspense thrillers go, Point Blank is pretty good."[14] Leonard Maltin gave the film three and a half stars: "Taut thriller, ignored in 1967, but now regarded as a top film of the decade."[15]

In the New York Times, Bosley Crowther described the movie as a "spectacularly stylized and vividly photographed film that hints at some of the complex organization and hideous humanity of the modern-day underworld" and that director Boorman had "done an amazing job of getting the look and smell of Los Angeles into the texture of his picture...But, holy smokes, what a candid and calculatedly sadistic film it is!....This is not a pretty picture for the youngsters--or, indeed, for anyone with indelicate taste."[16]

Slant reviewer Nick Schager notes in a 2003 review: "What makes Point Blank so extraordinary, however, is not its departures from genre conventions, but Boorman's virtuoso use of such unconventional avant-garde stylistics to saturate the proceedings with a classical noir mood of existential torpor and romanticized fatalism."[17]

The film holds a score of 93% on review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, based on 40 reviews with an average rating of 8.3/10. The website's critics consensus reads, "Shot with hard-hitting inventiveness and performed with pitiless cool by Lee Marvin, Point Blank is a revenge thriller that exemplifies the genre's strengths with extreme prejudice."[18] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 86 out of 100 based on 15 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[19]

Themes

[edit]Viewers and critics have often questioned whether or not the film is really a dream that Walker has after he is shot in the beginning. The film's director John Boorman claims to not have an opinion on the matter. "What it is, is what you see", responded Boorman. While filmmaker Steven Soderbergh has described Point Blank as "memory film" for Marvin. Boorman believes the film is about Lee Marvin's brutalizing experiences in World War II, which dehumanized him and left him desperately searching for his humanity.[6]

Critic David Thomson has written that the character of Walker is actually dead throughout the entire movie and the events of the film are a dream of the accumulating stages of revenge.[20] Others have also considered this concept; Brynn White has questioned whether or not Walker is a mortal or a ghost, "a vaporous embodiment of bitter vengeance barely clinging to Boorman's variegated frames" and Boorman has commented: "He could just as easily be a ghost or a shadow".[21] Some critics consider Point Blank, "a haunted, dream-like film that draws upon the spatial and temporal experiments of modernist European art cinema", especially the "time-fractured" films of French director Alain Resnais.[22][23]

Style

[edit]Point Blank combines elements of film noir with stylistic touches of the European nouvelle vague. The film features a fractured timeline (similar to the novel's non-linear structure), disconcerting narrative rhythms (long, slow passages contrasted with sudden outbursts of violence), and a carefully calculated use of film space (stylized compositions of concrete riverbeds, sweeping bridges, empty prison cells).[24][25] Boorman credits Marvin with coming up with a lot of the visual metaphors in the film.[6] Boorman said that as the film progressed, scenes would be filmed monochromatically around one color (the chilly blues and grays of Acker's apartment, Dickinson's butter yellow bathrobe, the startling red wall in Vernon's penthouse) to give the proceedings a "sort of unreality".[6][25]

To establish Walker's mythic stature, Soderbergh noted in the commentary, that the film cuts from a shot of Walker swimming from Alcatraz Island to a shot of him on a ferry overlooking the same island while a woman on the loudspeaker describes the impossibility of leaving the island. Soderbergh said that this contrast of the character's ease of escape with the loudspeaker's monologue makes the Walker character "mythic immediately".[6]

Legacy

[edit]Point Blank is hailed in the book 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die as "The perfect thriller in both form and vision."[26] Film historian David Thomson calls the film a masterpiece.[27] Thomson adds, "[...] this is not just a cool, violent pursuit film, it is a wistful dream and one of the great reflections on how movies are fantasies that we are reaching out for all the time—it's singin' in the rain again, the white lie that erases night."[28] Director Steven Soderbergh has said that he used stylistic touches from Point Blank many times in his filmmaking career.[6]

The Hunter was also the basis for Brian Helgeland's Payback (1999), starring Mel Gibson. Director Boorman has joked that Payback was so bad that Gibson must have taken the original script for Point Blank that Boorman and Marvin had thrown out.[6]

On March 29, 1968, Point Blank was screened at Cinelândia movie theaters in Brazil to protest the murder of 18-year-old high school student Edson Luís de Lima Souto by the military police of Rio de Janeiro. Souto was shot at point-blank range. Phrases such as "Do bullets kill hunger?", "Old people in power, young people in coffins", and "They killed a student... what if it was your son?" were written by protesters on the movie posters. The aftermath of Souto's death was one of the first major public protests against the Brazilian military government.[29]

Lee Marvin expressed consternation with his role in the film years later. In a 1983 interview, when about watching himself onscreen, he responded "How did I feel when I saw myself on the screen? I found it very unpleasant recently when I saw a film of mine called Point Blank, which was a violent film. We made it for the violence. I was shocked at how violent it was. Of course, that was ten, fifteen, eighteen years ago. When I saw the film I literally almost could not stand up, I was so weak. I did that? I am capable of that kind of violence? See, there is the fright; and this is why I think guys back off eventually. They say, 'No, I'm not going to put myself to those demons again.' The demon being the self."[30]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Thomas, Kevin (Jan 16, 1968). "CHARTOFF AND WINKLER: Entrepreneurs of the Offbeat Film Two Entrepreneurs of Offbeat Movies". Los Angeles Times. p. d1.

- ^ "Big Rental Films of 1968", Variety, 8 January 1969 p 15. Please note this figure is a rental accruing to distributors.

- ^ Point Blank at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- ^ "With "20,000 Leagues", the National Film Registry Reaches 700". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2019-05-21.

- ^ Winkler, Irwin (2019). A Life in Movies: Stories from Fifty Years in Hollywood (Kindle ed.). Abrams Press. pp. 306–318/3917.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m John Boorman and Steven Soderbergh (2005). Point Blank audio commentary (DVD). Turner Entertainment.

- ^ Winkler p 344-362/3917

- ^ Shea, Matt (February 6, 2009). "RETROSPECT: POINT BLANK (1967)" Archived 2011-07-16 at the Wayback Machine. Screentrek.com. Retrieved 2011-01-19.

- ^ a b The Rock: Part 1. [Featurette]. Alcatraz Island, San Francisco, California: MGM. 1968.

- ^ The Rock: Part 2. [Featurette]. Alcatraz Island, San Francisco, California: MGM. 1968.

- ^ Kael, Pauline (1968). Kiss Kiss Bang Bang. Atlantic Monthly Press. ISBN 0-7145-0658-3.

- ^ Kael, Pauline (1991). 5001 Nights at the Movies. Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 0-8050-1367-9.

- ^ Schickel, Richard; Simon, John, eds. (1968). Film 67/68: An Anthology by the National Society of Film Critics. Simon and Schuster.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (October 20, 1967). "Point Blank". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2022-11-05.

- ^ Maltin, Leonard (August 2008). Leonard Maltin's Movie Guide (2009 ed.). New York: Penguin Group. p. 1081. ISBN 978-0-452-28978-9.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (19 September 1967). "Vengeful Lee Marvin in Point Blank". The New York Times.

- ^ Schager, Nick (July 24, 2003). "Point Blank". Slant Magazine. Retrieved 2007-09-21.

- ^ "Point Blank". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved 2024-04-07.

- ^ "Point Blank (1967) Reviews". Metacritic. Fandom, Inc. Retrieved July 7, 2023.

- ^ Thomson, David (2012). The Big Screen: The Story of the Movies. New York: Macmillan. p. 406. ISBN 978-0-374-19189-4. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- ^ Ruffles, Tom (2004). Ghost Images: Cinema of the Afterlife. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. p. 237. ISBN 0-7864-2005-7. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- ^ Danks, Adrian (6 October 2014). "A Man Out of Time: John Boorman and Lee Marvin's Point Blank". Senses of Cinema. Film Victoria, Australia. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- ^ Erickson, Glenn. "Point Blank". TCM Classic Movies. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ The Hunter: A Parker Novel, University of Chicago Press, accessed 03 July 2020

- ^ a b Applegate, Tim (2002). "Remaking Point Blank". The Film Journal (8). Retrieved 2011-01-19.

- ^ Schneider, Stephen Jay (Editor) (October 1, 2008). 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die (Fifth ed.). Hauppauge, New York: Barron's Educational Series. p. 472. ISBN 978-0-7641-6151-3.

- ^ Thomson, David (October 26, 2010). The New Biographical Dictionary of Film: Fifth Edition, Completely Updated and Expanded (Hardcover ed.). Knopf. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-307-27174-7.

- ^ Thomson, David (October 14, 2008). "Have You Seen . . . ?": A Personal Introduction to 1,000 Films. New York: Random House. p. 680. ISBN 978-0-307-26461-9.

- ^ (in Portuguese) "Brasil 1968: "Mataram um estudante. Podia ser seu filho". Esquerda.Net. May 12, 2008. (originally published in O Globo on March 2, 2008).

- ^ Woodruff, Paul (2001). Facing Evil: Confronting the Dreadful Power Behind Genocide, Terrorism, and Cruelty. Peru, Illinois: Open Court Publishing. p. 7. ISBN 0-8126-9517-8. Retrieved 1 January 2024.

External links

[edit]- Point Blank at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- Point Blank at IMDb

- Point Blank at the TCM Movie Database

- 1967 films

- 1960s crime thriller films

- American crime thriller films

- American gangster films

- Films scored by Johnny Mandel

- American films about revenge

- Films based on American novels

- Films based on crime novels

- Films based on works by Donald E. Westlake

- Films directed by John Boorman

- Films set in California

- Films set in San Francisco

- Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer films

- Films produced by Robert Chartoff

- Films produced by Irwin Winkler

- United States National Film Registry films

- American neo-noir films

- Films about contract killing in the United States

- 1960s English-language films

- 1960s American films

- English-language crime thriller films